If You’re In a Pothole, Don’t Dig A Sinkhole! | Crisis Communications

You’ve probably heard this classic crisis communications chestnut: “If you’re in a hole, stop digging.”

Put another way, if you’ve already driven into a bumpy pothole, your goal is to avoid turning it into a massive sinkhole that swallows your reputation whole.

Every crisis is different, but I’ve repeatedly seen certain patterns play out that unnecessarily turn potholes into sinkholes. This post breaks down five of the most common—and while some of these crises began as something much larger than a pothole, they were made that much worse by a bad response.

1. Offering an Insufficient First Apology

In The Media Training Bible (buy now!), I wrote:

“Many executives are reluctant to issue a full and unequivocal apology after making a mistake. That’s not because they’re bad or uncaring people. More commonly, it’s a human reaction from a defensive person who feels that his or her well-intentioned motives were misunderstood.

As a result, the executive usually issues a hedged “half apology” that goes something like this:

“If you were offended by what I said, then I am sorry.”

That type of “if/then” apology, which places the burden on the offended person rather than the offender, tends to inflame a crisis instead of ending it. The equivocation almost inevitably fails to satisfy the public, forcing the executive to issue a second, more complete apology several days later:

“I said something offensive, and I apologize. I listened carefully to your feedback and completely understand your reaction. I will learn from my mistake to make sure it doesn’t happen again. I sincerely apologize.”

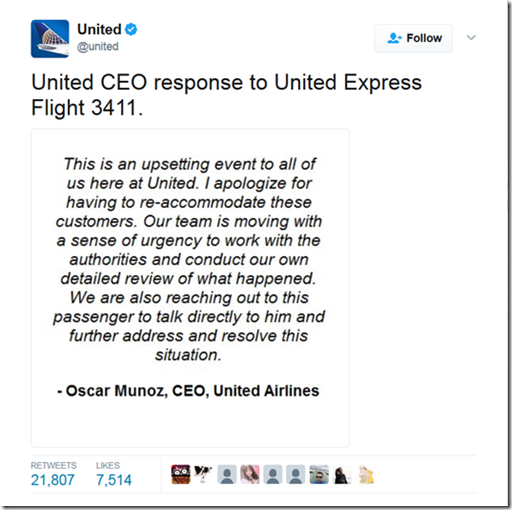

When United Airlines dragged a paying customer off its flight earlier this year because it had overbooked the plane, CEO Oscar Munoz stepped right into this predictable trap. Here’s his first apology:

Critics rightly seized on his use of the term “re-accommodate” — as if the problem was a mere travel glitch, not a badly beaten and bloodied paying customer — and forced Munoz to try again. He was better in this second attempt — but the effectiveness of the second apology was far less than it would have been had he used this approach first.

2. Missing The Point

Munoz missed the point with his “re-accommodation” euphemism, which attempted to sidestep the real issue that caused the public furor to begin with. He was far from alone.

Televangelist Joel Osteen made a similar mistake when he attempted to evade responsibility for keeping his mega-church closed after Hurricane Harvey hit Houston in August.

His justifications included that: the City of Houston hadn’t asked him to set up a shelter; there was another shelter four miles away with a 10,000-person capacity that he never imagined would fill; his Lakewood Church was close to flooding itself; and the logistical and staffing challenges of opening Lakewood immediately would have been enormous and couldn’t have been done immediately.

But he missed the point—that a man worth $56 million with a 16,800-seat arena who professes to be a man of God in service to others should have been willing to make Herculean efforts to help in any way he could—and he didn’t.

3. Trying To Excuse The Behavior Away

After celebrity chef Paula Deen admitted to using racial slurs in 2013, her company issued a statement that read:

“She was born 60 years ago, when America’s South had schools that were segregated, different bathrooms, different restaurants and Americans rode in different parts of the bus.”

Her company, working on her behalf, tried to cast her as a victim of the society in which she was raised, as if many other southerners didn’t know better and didn’t replicate her behavior despite similar upbringings.

More recently, Kevin Spacey trotted out this gem when he was accused of sexual assault against actor Anthony Rapp, the first of what would become many accusers:

“If I did behave then as he describes, I owe him the sincerest apology for what would have been deeply inappropriate drunken behavior.”

When actor Richard Dreyfuss was accused of sexual assault, his statement read, in part:

“At the height of my fame in the late 1970s I became an asshole – the kind of performative masculine man my father had modeled for me to be.”

This was offered less as an excuse than an explanation—but it also cleverly shifted some of the blame onto his father (and conveniently ignored that he was a 30-something man when these alleged acts occurred).

Efforts to contextualize prior bad actions are difficult at best—and backfire badly at worst. Even if everything above is true, it usually only serves to add fuel to the fire. In fairness, there may be times when explanations do more good than harm. But before deciding to use one, remember the acronym conceived by behavior change specialist Jerry Sternin: TBU, or “true but useless.” If it’s true but unlikely to move minds, strike it from your statement.

4. Taking Too Long To Respond

When Equifax announced a data breach that affected 143 million Americans, the company released an initial statement—and then stopped communicating for days. According to The Atlantic:

“The announcement of the breach, which came after hours on Thursday, offered the first sign of indifference. Media outlets, including The Atlantic, rushed to cover the matter, but details were slim. When my colleague Gillian White contacted them, Equifax offered no further comment beyond the materials they had published on an informational website. Other outlets experienced similar silence.”

What made that particularly confusing is that the company knew about the breach weeks before announcing it, meaning they had plenty of time to prepare a more complete response and keep the lines of communication open. As Dorothy Crenshaw wrote on her ImPRessions blog:

“The site it set up for customer inquiries was quickly overwhelmed, and after the initial statement, the CEO did not formally respond until four days after the announcement.”

This fourth point could have easily been another: failing to provide victims with support or a meaningful remedy. In this case, the panicked reaction of Americans concerned about their personally identifiable information only got worse when remedies intended to solve the issue came with technical errors, new security risks, and legal language restricting consumers’ right to sue.

5. Disrespecting The Victims

This one is painfully obvious, right? And yet…it happens more often than you’d think. United’s Oscar Munoz called the passenger “disruptive” and “belligerent” before backing away from those claims and trying again.

British Petroleum’s former CEO, Tony Hayward, famously announced, “I’d like my life back” during his company’s massive 2010 oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. That statement was seen as particularly tone deaf toward the 11 men who lost their lives on his company’s oil rig.

The worst of the lot comes from 2013 when, just days after more than 40 people were killed when a 73-car train filled with oil derailed in Quebec and slammed into downtown Lac-Mégantic, Edward Burkhardt — the chairman of Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railways — came into town to address locals.

Here’s the beauty he dropped during his press conference:

“I thought people would respond to my willingness to come there…I mean, they were screaming about how I took three days to get there…People wanted to throw stones at me. I showed up and they threw stones. But that doesn’t accomplish anything.”

Sometimes, letting them throw stones is appropriate and necessary to begin the process of moving forward in a crisis. It should go without saying that offering a sympathetic ear and pledging your support is also just the right thing to do.

Kevin Spacey photo via Wikimedia Commons user Pinguino k.

Brad

I genuinely like Joel Osteen so it was hard to watch him have difficulty with answering the challenging questions. None of the reporters were able to show that his answers were not truthful. If you assume that Joel told the truth, how could he have improved his response. It is not easy to make the truth seem truthful when you are saying it to an audience that wants you to fail.

Dave

Hi Dave,

There’s no single answer to that question, but one place I saw an opportunity for improvement was for him to have promised to meet with city and state authorities when Harvey was over to proactively develop a specific plan to use his building as a shelter for any future storms. To my knowledge, he didn’t say that during any of his interviews.

Thank you for reading!

Brad