Why A Textbook Crisis Apology Failed to Satisfy Book Critics

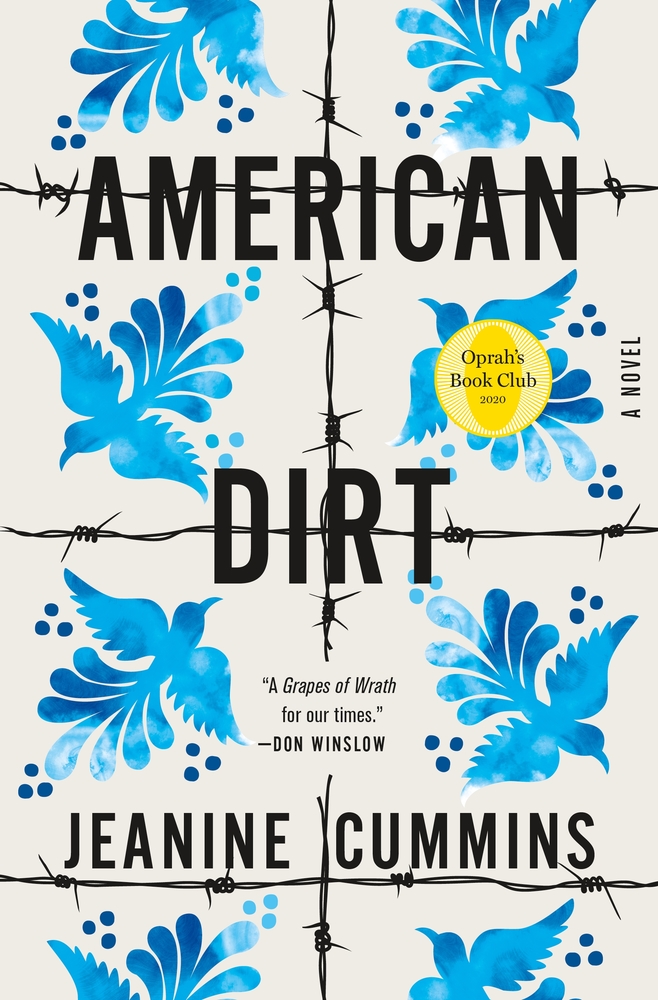

Flatiron Books thought it had a winner on its hands with American Dirt, a story about the Mexican immigrant experience.

Flatiron Books thought it had a winner on its hands with American Dirt, a story about the Mexican immigrant experience.

And, it does. Championed early by some literary heavyweights, the book is on pace to become one of the year’s top sellers. But such success comes amid controversy related to charges of cultural appropriation and insensitivity.

Critics, including other writers, say the story of a Mexican mother and her son escaping a ruthless drug cartel by fleeing to the U.S. border is stereotypical and racist. The book has also kicked up the debate over who gets to tell the story of a migrant Latino experience. The author, Jeanine Cummins, who is of Irish and Puerto Rican descent, readily admits to being non-Mexican and not a migrant.

As a result, the publisher Bob Miller apologized. The company released his statement late last month, including this post on Twitter. You can read it by clicking the following image:

Statement from Bob Miller (President & Publisher, Flatiron Books) regarding AMERICAN DIRT: pic.twitter.com/S4sQetyS2s

— Flatiron Books (@Flatironbooks) January 29, 2020

At first glance, the apology appears to be a textbook atonement for the concerns the Latino and publishing communities have raised. The reaction on Twitter, however, was overwhelmingly negative.

Critics largely bashed what they saw as an insincere and disingenuous effort. Dozens further derided Flatiron Books‘ decision to cancel the book tour because of “threats of physical violence” against the author and booksellers, given no specific threats were revealed. Commentators largely saw it as a cop out for the bad press the company didn’t expect to receive.

Granted, with social media, these digital pile-ons can quickly become vitriolic and emblematic of a “cancel culture.” But, do these critics have a point?

In this post, we’ll show you where the publishing company got it right and where it could have done things differently.

Where the apology works

When making a public – or private, for that matter – mea culpa, there are certain elements that can make it far more successful, effective and enduring. We’ve listed several ways Flatiron Books delivered.

- The company was clear in its accountability. If Miller had used vague sentences such as “Mistakes were made,” or “Failures do and can happen,” it could have suggested a distancing from the offense. Instead, he says, “We made serious mistakes.” People want to hear that you are taking responsibility for what happened. Some researchers have found if you can only include one element in an apology, this is the most effective one.

- Miller cites specific offenses. A less-than-specific apology may make your intended audience wonder if you know what you are apologizing for. He writes: “We should never have claimed that it was a novel that defined the migrant experience; we should not have said that Jeanine’s husband was an undocumented immigrant while not specifying he was from Ireland; we should not have had a centerpiece at our bookseller dinner last May that replicated the book jacket so tastelessly …”

- The firm conveys regret. Miller notes that such actions were insensitive and expresses remorse for the company’s decisions. Expressions of regret and remorse reveal that you recognize your own behavior and, more importantly, how that behavior caused another to feel hurt or become angry.

- Miller provides reassurance that things will change. He suggests that the controversy has revealed areas where the company needs to do more. “Simply put, we wish to listen, learn, and do better,” he writes. He follows that with a commitment that the company will address issues about representation in the “books we publish and the teams that work on them.” He also promises a series of town hall meetings with the author. Anecdotally and empirically, the best apologies include an offer to make things right and a promise that it won’t happen again.

Where the apology could be better

The best apologies work to reduce the offense and repair the rift. There are some elements of this apology that were less effective in reaching that goal. We’ve listed several areas that could have been improved.

- The apology could have begun with a lot more humility. After only nine words devoted to the backlash, the company goes on to tout the book for 90 more. While it is important to provide context and explanation for why something went wrong, the introductory paragraph runs the risk of negating the statements of accountability and remorse that follow. One could read it as a rebuke to those who have been critical: We don’t understand why you feel this way, given how many people have lavished praise on this book. Or, it could suggest that the company still doesn’t truly own the mistake: We are just flabbergasted by the response. However, we do understand people are upset, so here is an apology.

- Is the apology properly aligned? The most effective apologies address the proper audience with the proper message. Given most of the apology focuses on the company’s missteps in “positioning” the novel, it’s not a stretch to see how the apology could be read as the company making an apology to itself for getting that part wrong, rather than more direct mea culpa for the anger and hurt it caused among the Latino and publishing communities.

- Can critics point to a lack of empathy? To truly understand how your audience feels, you need to see the crisis from their perspective. You need to have empathy. Although Flatiron Books owns up to a lack of broader perspectives within the company, the statement doesn’t completely address the charges of stereotyping, racism, insensitivity, and cultural appropriation that caused the uproar.

- Did the company sound defensive? Detractors charged the company with turning the blame on the very people they were presumably apologizing to by a.) labeling what critics saw as well-placed criticism “vitriolic rancor,” and b.) suggesting the critics’ lack of respect for the author and her work had prevented a meaningful two-way dialogue. Although that may not have been Flatiron Books intent, in general, apologies are less effective if you attempt to apologize and defend yourself at the same time.

Apologies in the Digital Age

There is something to be said for the difficulties in apologizing in the social media era. Everyone is a critic, with a platform to the world. Even if a company does issue a perfect apology, someone or millions of “someones” can find fault.

Here’s just sampling of online critiques to Flatiron Books’ statement:

One Twitter user, New Jersey-based author Nisha Sharma, went so far as to mark up the statement with suggested edits:

I tried to fix it but it’s garbage, so 🤷🏽♀ pic.twitter.com/LlHQnNlz14

— Nisha (is on deadline again) Sharma (@Nishawrites) January 30, 2020

As part of your crisis communication plan, it’s important to adequately assess the critiques. How deep is the push-back – a few vocal activists or representatives of a far larger group? Who needs your apology – the ones who specifically called out the gaffes, or the broader online community? Since an apology will never satisfy everyone, who do you most hope to reach?

In the case of Flatiron Books, we suspect the apology was not aimed at those who thought too much had been made of the flap, nor those who really liked the book. So, if it was meant to assuage the discontent of those who felt they were misrepresented, was the apology all it could have been?

Time will tell whether the company’s statement, and its future actions, effectively address concerns that have been raised. However, one sign indicates the company’s desire “to listen, learn, and do better,” is not just lip service.

Last week, leaders of #DignidadLiteraria, a movement critical of the book, met with the publisher. For their part, leaders of the movement were encouraged, calling the meeting a “victory” for their calls for change.