Media Relations: When Should You Take A Five-Yard Loss?

I recently worked with an organization that has a vocal, effective, and often sympathetic opponent.

The opponent is a “David” — a small group perceived to be fighting for a fair cause — while the organization is perceived, fairly or not, to be the unfeeling “Goliath.”

When the Goliath receives media inquiries, they reply with a written statement. They’ve calculated that the risks of combating the David through an unpredictable on-camera interview are too high and that a misstatement would only give David more fodder to use against them.

The problem is that the David accepts on-camera interviews, which ends up painting a stark contrast between the two parties. News stories show a video clip from David’s on-camera interview, which is then butted up against the correspondent having to read, in voice over, the Goliath’s statement from an on-screen graphic. It’s easy to imagine viewers concluding that the David is as open and reasonable as the Goliath is cold and distant.

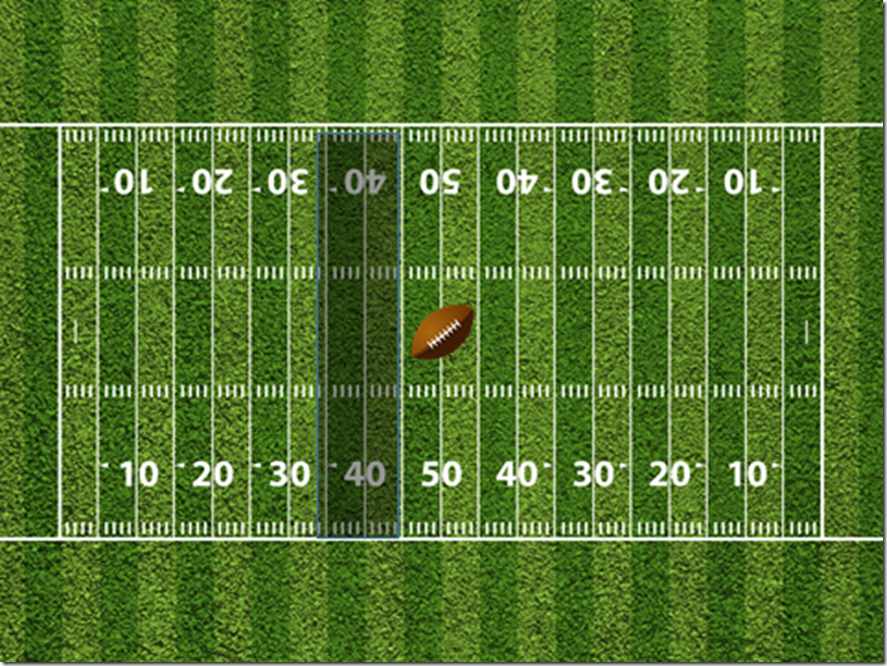

By refusing to appear on camera, the Goliath is taking a five-yard loss in every interview. But are there times when a five-yard loss is an acceptable outcome?

The image above suggests that the written-statement approach leads to a loss of yardage every time the ball is snapped. But it also shows something else: that the potential loss is contained. They’re not getting sacked and losing 30 yards on each play — just a few. Sure, they may never actually move the ball forward — but if risk tolerance is low, a small loss may be acceptable.

Instead, let’s say they decided to appear on camera when interview requests came in. The playing field might look more like this:

Suddenly, the potential loss is much greater. An unfortunate gaffe will be used relentlessly by the David to weaken the Goliath. Beyond that, the Goliath is walking into a media environment in which “Davids” are often granted more sympathy automatically. BUT, as you see in the image above, there’s also the chance to make a meaningful gain.

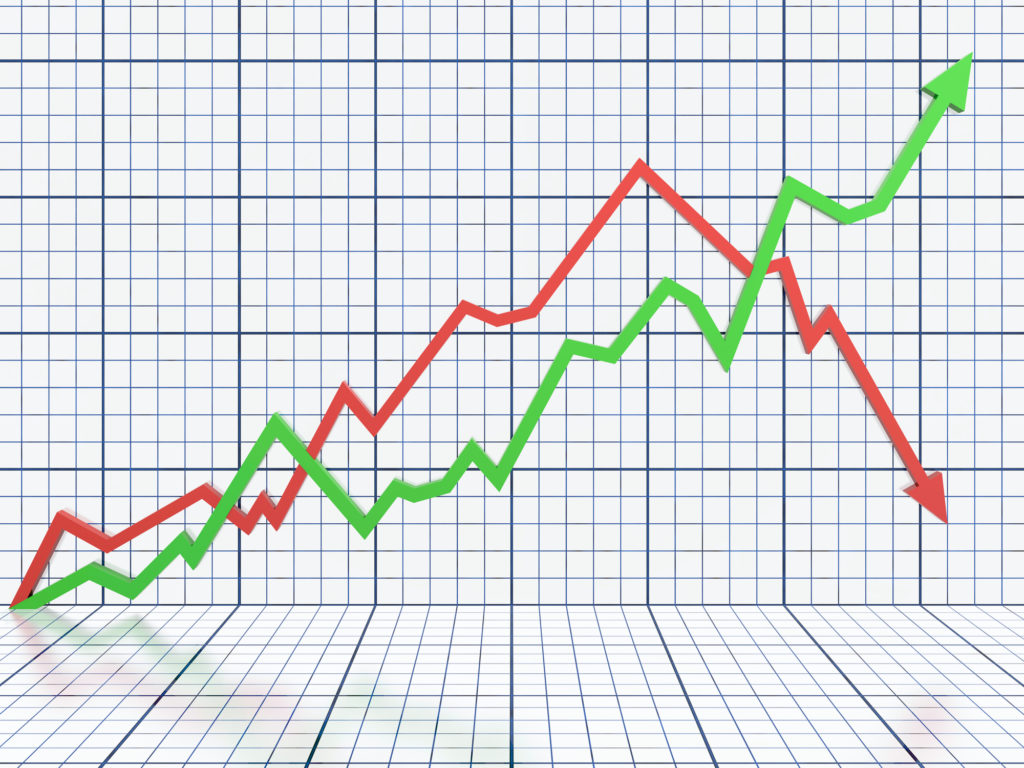

In investing terms, one might put it this way:

Option one is like investing in your bank’s savings account. You’ll make a few dollars in interest, but they won’t be enough to keep up with inflation, meaning you’ll ultimately lose money—but only a little.

Option two is more like stock investing. The potential gains are tempting and possibly great, but the downside is too real to be ignored.

Back to my original question: Are there times when a five-yard loss is a more acceptable outcome? I can think of a few cases in which the answer might be yes:

- Despite your public perception being diminished with a series of five-yard losses, you calculate that you’re still more likely to accomplish your goals by reducing your risks than by magnifying them.

- Your spokespeople aren’t as empathetic, credible, or dependable as they’d need to be to provide a useful counterbalance to the David. (Possible solution: Provide them with professional media training!)

- The investment of time in redeploying personnel to prepare for and respond to media requests would take them away from higher-value tasks. (Possible solutions: Accept only the highest-priority interviews and/or expand the pool of potential spokespersons.)

While there may be times in which a written statement remains the best approach, I’ll close with two final thoughts.

- Challenge yourself to ask whether your tendency to respond in writing is due primarily to deliberate strategy or to a combination of habit, fear, or laziness.

- Remember the power of cognitive dissonance. One of the best ways to neutralize a more sympathetic opponent is to show the audience that you, too, are as warm, reasonable, thoughtful, and relatable as your opponent. Those traits can help shift an audience’s thinking in ways that written statements never could.

Brad….an underpinning of this David & Goliath scenario is the validity of David’s statements. Sometimes replying to various charges, rumors, etc. lends credence to them.

POTUS is a prime example of over responding to everything that makes a noise.

It’s important for companies to pick their fights rather than the reverse. News Releases can also have a backgrounder/fact sheet attached outlining positives from the company.

I like these ideas Brad. Thanks.

There’s another strategy we copywriters employ (admittedly not while in a ‘crisis control’ mode) to intentionally polarize a general audience… and sift the wheat from the chaff. Often done in lead acquisition marketing campaigns.

Done strategically – even within the context covered in your article – this polarizing approach can strengthen relationships with desired target market segments (wheat) – while repelling unwanted segments (chaff). Win more winners – lose more losers!

Sometimes further controversy is needed to shift public focus and attention.

I also employ radical honesty as a strategy – for attracting and repelling different segments of a general audience in the one media piece.

That said – there is no book of ‘right and wrong’ for this in my opinion. All approaches are possible strategies and can be tested in small media markets before rolling out to bigger audiences (when time-sensitivity is not so critical).

[…] To do: Read his advice on what can happen when you choose a live interview over a prepared statement. See his article “Media Relations: When Should You Take a Five-Yard Loss?” […]