If I Can’t Veto Your Questions, I’m Canceling This Interview

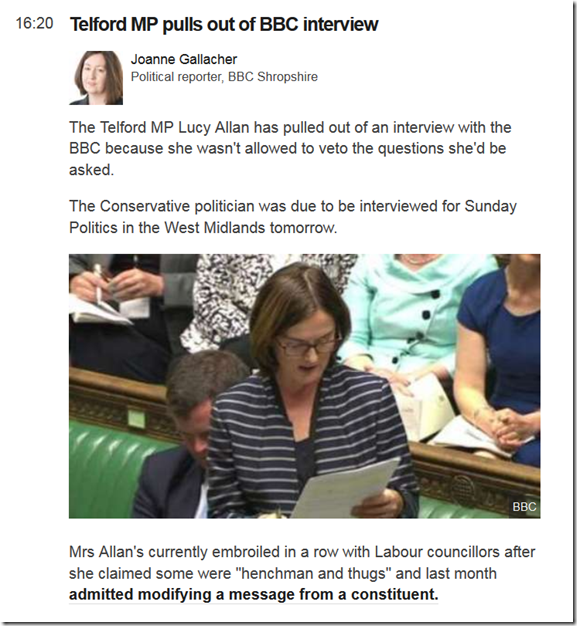

Lucy Allan, an MP (Member of the British Parliament) for Telford, Shropshire, has been getting a lot of negative press lately. Among other things, she has been accused of bullying her staff and doctoring a constituent’s Facebook post by adding a death threat (she admitted to the latter).

Last week, she was scheduled to appear on the BBC—but reportedly pulled out because she wasn’t allowed to veto certain questions in advance. Here’s how the BBC covered it:

The Independent ran a similar headline:

According to The Independent:

Lucy Allan, the MP for Telford, told BBC Shropshire that she wanted to be “sure that malicious false allegations made by ‘aliases’ were not repeated as if fact on a mainstream serious political programme”.

My reading of that statement is that Ms. Allen was trying to prevent questions such as:

“Many of your critics say you have a long history of bullying, and need to resign. What would you say to them?”

In other words, she didn’t want accusations embedded into a question if she deemed those accusations to be false. But of course, such questions are standard and predictable—and the way to handle them is to prepare in advance to rebut them.

Ms. Allan denies that she canceled the interview over a veto threat, tweeting that the BBC had “slurred” her by suggesting otherwise. She also said that she has written evidence to reinforce her claim—but as of this writing, I was unable to find that she had offered it (neither her own website, nor a news search, nor her Twitter feed offered her supposed evidence; she also didn’t respond to my tweet requesting clarification).

The Risks of Setting Interview Conditions

In an earlier post, I wrote about seven “reasonable pre-conditions” spokespersons and PR pros can (occasionally) request prior to an interview. One of them is indeed negotiating the topics that can (and cannot) be discussed. But such conversations should occur before an interview is agreed to, not after, and they come with the following critical risks I identified at the time:

“You can request to limit the interview either to topics you do want to discuss (e.g. a basketball coach who wants to discuss his team’s latest game), or to avoid topics you don’t want to discuss (e.g. your star center’s recent drunk driving arrest). But even if reporters agree to such a pre-condition, they often disclose the very pre-condition to their audiences (in some cases, they’re ethically bound to do so). So before you make such a request, ask yourself whether that disclosure could be more damaging than answering the tough questions.”

The mere request for an interview condition can be reported, making the spokesperson appear evasive or dishonest. That’s especially true in this case, in which a person accused of bullying engaged in what can be seen as similar behavior. And even the reporter agrees to abide by such rules, nothing prevents them from violating them when the cameras start to roll (other than professional ethics, which occasionally get skirted).

If you agree to the interview, you have the power to “veto” questions during the interview. You can do that by acknowledging the heart of the question and then transitioning to something else (I discuss that technique in my media bridging series here). As an example, she could say:

“I’m passionate about my work, and occasionally that passion comes out as anger and impatience. I’ve apologized privately for some of the things I’ve said and I’ll do so publicly again right now. But I think this story has been covered a lot already, and I have nothing to add beyond what I’ve already said. Therefore, I’d like to discuss the issues affecting my constituents.”

Journalists may or may not let it go at that—but good spokespersons know how to diffuse persistent follow-up questions. As for whether Ms. Allan’s constituents would punish her perceived evasions, that depends. If a sufficient number of Allan’s supporters share her view that the reporting has been disproportionate or unfair, they’ll cheer her refusal to play by the media’s rules. If they don’t, they’ll punish her for her lack of forthrightness—in which case I’d question why she accepted the interview in the first place.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons user Redchoir

Like the blog? Read the book! A free sample of The Media Training Bible is below.