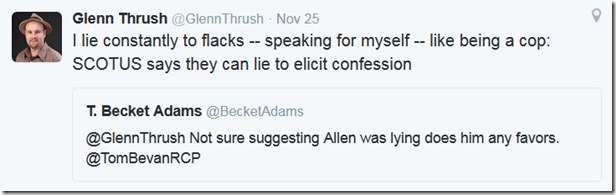

One Reporter’s Surprising Admission: "I Lie Constantly"

Glenn Thrush, the Chief Political Correspondent for Politico, sent several surprising tweets last week about the promises reporters make—and break—with communications staffers arranging interviews with their principals.

His main argument? It’s acceptable to “lie” to PR pros by promising a favorable story in exchange for access—and then doing the story you want to do anyway.

I’ll let others debate whether or not such lies are acceptable. My interest is less in serving as an arbiter of journalistic ethics than in offering some insight into the mind of a journalist.

Mr. Thrush’s frankness surprised me at first—his blunt (if tongue-in-cheek) tone seemed a bit shocking. But the more I thought about his message, the more I realized he was just saying out loud what most experienced PR pros have encountered at some point in their career.

And, from a reporter’s point of view, I’m not sure he’s wrong.

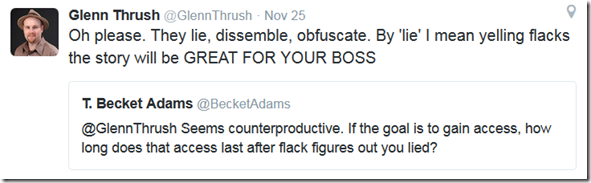

A reporter’s primary function is to get the story. It’s easy to see how political journalists, tasked with reporting stories in the public interest but facing a climate filled with spin, subterfuge, and misdirection, might be tempted to fudge the agreements they make when setting up interviews.

Skirting those agreements may be necessary to expose wrongdoing. Reporters who give PR pros advance warning about an unfavorable allegation may find themselves denied access to a principal. And even if the interview is approved, the principal will have had time to compose a carefully crafted response, denying the public an honest response to a difficult charge.

But to (partially) paraphrase Mark Twain, there are lies and damn lies. Reporters who regularly commit the latter will likely find themselves denied future access, reducing their ability to report as effectively.

What Does This Mean For You?

When I conduct practice interviews with our clients, I often land on a challenging topic and watch the spokesperson begin to obfuscate. Sometimes, I didn’t even plan on asking a follow-up question—but the spokesperson’s limp initial response tells me there’s a fuller explanation behind it. Whether I had made an “agreement” in advance of the interview or not, I would still press on and ask the follow up. It’s my job. I’m motivated by a desire to cut through the spin and get to the real answer.

Therefore, go into interviews with your eyes open. Recognize that some reporters—whether motivated by honest news motives or not—may break the rules. Although you can try to enforce the rules during the interview (“You said we weren’t going to talk about that!”), doing so might make you look worse than just answering the questions despite the broken deal.

Prepare for the interview as if no deal exists and assume you will be hit with unexpectedly difficult questions. As Mr. Thrush’s tweets make clear, those are very real possibilities.

What do you think? Please leave your thoughts in the comments section below.

I think there are a lot of hairs to split on this one, the least not being that you have to distinguish DC goings-on from the rest of Planet Earth. Obtaining an interview under false pretenses is against the ethics polices of most major news organizations. Of course those rules are regularly broken in ways subtle or otherwise; but that’s not what’s important. What’s important is that every quality PR pro knows that no real reporter will blatantly agree to interview pre-conditions. Of course there are winks and nods, especially in cut-throat locations like our nation’s capitol.

Only a fool or his client goes into an interview thinking some things are off-limits. Call it the “60 Minutes syndrome” – how many times has that show simply let a newsmaker dig their own grave?

In my journalistic career, I had interviewed controversial politicians along with celebrities, handy with their own spins. Once trust is established in a relationship (especially in a small market), addressing the issues and questions with you becomes preferable to the interviewee fielding ones coming from someone who has the reputation for being notoriously inaccurate or inarticulate in representing the response. I did much preliminary research, was upfront with what I would ask, etc. and went above and beyond to provide a balanced account. I once had the opportunity to interview a controversial congressman who stopped in our city. Had to grab him on the run and asked point blank about some allegations. He handled it very quickly and smoothly, obviously used to engaging in dismissiveness. That’s another thing. When the person being interviewed has already faced years of “lies,” in order for the reporters to gain access, they learn to articulate their answers in rapier fashion and to their own benefit.

If any PR pro thinks the journo will stick to ANY rules they are not a PR pro.

That said, in a non-political arena, relations with us flacks are important or you ain’t getting any more interviews.

Also, if the relationship is short and was full of empty promises to begin with, the flack has to know this, they can also research articles and take them out to lunch and see the journo’s personality… basic media relations… people stuff!

Ethics will differ among individuals, it’s all up to the relationship to work things out… nothing new there either.

fomil is spot on about “off limits” and JR is spot on about “liar” journo reputations…