Media Training Report 6: Ten Advanced Media Interviewing Tips (Part Two)

In our previous report, we offered five advanced media interviewing tips and techniques to deploy in your more challenging moments. We’re back with another five that cover equally thorny situations. For instance:

- How do you respond to a reporter who is trying to get a rise out of you with a well-placed, provocative word?

- How do you handle a question that is inherently incorrect?

- How do you respond to the charge when you’ve been accused?

When challenged, criticized, or caught in a tense media moment, remember this: You have the tools to construct a much better outcome.

Five (More) Advanced Media Interviewing Tips

6. How to Flip a Leading Question

When it comes to money, being loaded is not such a bad thing. When it comes to a media interview, loaded questions are hardly ever a good thing.

Loaded language elicits strong feelings – often inducing immediate emotional reactions among readers and listeners. That is why reporters use such language when asking questions of their sources. To use a loaded term of our own, they attempt to goad you into having an emotional response to a negative term embedded in the question.

For instance, they might opt for the word “slash” over the less visceral “reduce” for a question about cost cuts. Or, they might wonder why you “eliminated” school programs, rather than the tamer term, “reduced.”

You are far from powerless to this technique, however. By learning how to flip the word in your favor, you can offer a rather pointed response of your own. You do this by redefining the word, rather than denying the negative term. When you concentrate on making a positive case for your position, you don’t waste precious time disagreeing with the reporter’s characterization.

Here are some examples of how to flip (the loaded words are in bold):

Example No. 1

Say you are a mayor being interviewed by a reporter about damaging floods that occurred in your city.

She asks:

“If you are so concerned about the flooding, why have you refused to accept the funds for rebuilding?”

Your response:

“What I am refusing to do is accept grants that could end up costing our community more. We need a clearer picture of whether this funding will require us to change our building and zoning codes. I am all for giving relief where relief is due, but before we, as a community, say ‘yes’ to the offer, we need to know if that means we can’t say ‘no’ to certain building projects in the future.”

Example No. 2

You are a CEO of a large manufacturing company that has announced the closing of two plants and the loss of 150 jobs. You are being interviewed about the decision.

The reporter asks:

“We know the closings will deeply affect the workers and the communities in which these plants were based, but you’ve offered few specifics as to why you are shutting them down. Is mismanagement to blame?”

Your response:

“It’s quite the opposite. It would be mismanagement if we were to keep these facilities open. We have thousands of employees spread out across the country, and to keep the company viable, vibrant, and producing, we must streamline our operations. That said, we understand the severe impact this decision has caused for our employees at these facilities. We do not take these decisions lightly, and we are currently working to relocate workers to other positions in the company.”

7. How to Dismantle a False Frame Question

They often sound logical enough, but there is a type of question posed by reporters that contains a serious flaw – an incorrect assumption that lies at the heart of the query.

This advanced media interview training tip allows you to deftly contradict the interviewer, but also “reframe” the question by rebutting the assumption and making your case positively and confidently.

Example No. 1

One of our clients, an executive at a manufacturing company, was excited about an innovative safety feature that was about to be introduced into one of the company’s existing products. Given his competitors were years away from introducing the same technology, he was certain his company would gain a meaningful competitive advantage.

He also was nervous, however, knowing that by touting the new feature, he would inevitably be faced with questions from customers and reporters about the safety of the millions of products his company had already sold. Without this new safety device, were those older products any less safe? Were they dangerous?

The question he feared most was this:

“What would you say to one of your customers who purchased one of your older — and therefore less safe — products?”

So, we casually asked him whether he viewed the older products as unsafe. “Absolutely not,” he said. “Best in the marketplace. But the new ones are even safer.”

His answer revealed that his most dreaded question was a classic “false frame” question. It contained an assumption that may have sounded logical, but ultimately was incorrect. He had to create a new frame. To do that, he needed to follow a two-step process:

- Dispatch with the fallacy

- Move to the message he really wanted his audience to hear

This was his rebuttal:

“I disagree with that premise. A car with six airbags is safe; a car with eight is that much safer. Our customers should know that the products of ours they already own are among the safest in the marketplace — and that when they decide to get a new model, it will include yet another great safety feature.”

8. How to Walk the Ladder

What does a ladder have to do with tricky media situations?

When it is the metaphorical one that we offer here, it can help you to determine if it’s best to delve into the details or take a big-picture approach when responding to challenging questions. Here’s how it works:

In his 1949 book Language in Thought and Action, linguist S.I. Hayakawa describes what he called the “Abstraction Ladder.” The bottom rungs of the ladder represent the most concrete ideas or objects (he offers the example of a cow named Bessie), while the top rungs represent more abstract concepts (in this example, “livestock” and “farm asset” are the more abstract descriptors of the cow).

The ladder, and the concept of concrete versus abstract, provides you with a tool to answer more difficult questions by placing them on the proper rung. Is the query abstract or concrete (or specific)? Once you have determined their place, you go to the opposite end in your response. In other words, a vague question merits specific examples; a specific query is put in the context of the larger picture.

There are several scenarios where this is particularly helpful.

Example No. 1

You are a school superintendent who has proposed a budget with a $6 million increase over the previous year. That means high taxes, and, predictably, the community is not happy. During a town meeting, residents blast the proposal, accusing you of overspending millions of dollars (abstract). You answer by highlighting several popular community programs and how the rise in their costs shaped the budget (concrete). This has the effect of reminding people that the budget is more than just a dollar figure, but rather funds that support the programs the community has come to expect.

Example No. 2

Apple founder Steve Jobs

Steve Jobs, the late founder of Apple, effectively changed the level of abstraction when he was asked a pointed question by an audience member at a technology conference.

The audience member said:

“It’s clear and sad that on several counts you discussed, you don’t know what you’re talking about. I would like, for example, for you to express in clear terms how, say, Java, in any of its incarnations, addresses the ideas embodied in OpenDoc. And when you’re finished with that, perhaps you can tell us what you personally have been doing for the past seven years.”

This was Jobs’ response:

“One of the hardest things when you’re trying to effect change is that people like this gentleman are right in some areas. I’m sure that there are some things that OpenDoc does, probably even more that I’m not familiar with, that nothing else out there does. And I’m sure that you can make some demos, maybe a small commercial app, that demonstrates those things.

The hardest thing is how does that fit into a cohesive larger vision that’s gonna to allow you to sell $8 billion, $10 billion of product a year? And one of the things I’ve always found is that you’ve gotta start with the customer experience and work backwards to the technology … and as we have tried to come up with a strategy and a vision for Apple, it started with, ‘What incredible benefits can we give to the customer, where can we take the customer?’ not starting with, ‘Let’s sit down with the engineers and figure out what awesome technology we have and then how are we going to market that.’ And I think that’s the right path to take.”

At the beginning of his answer, Jobs addressed the questioner’s accusation directly by conceding he didn’t know everything about OpenDoc (concrete). But he quickly transitioned away from the negative question and reframed the subjects of the query, Java and OpenDoc, into a larger framework — Apple’s overall product development strategy (abstract).

9. How to Lean Into Accusations

No matter how you slice it – Old English, Latin, French – the etymology of the word accuse isn’t pretty. It hasn’t lost much of its punch over the centuries – it’s long held the meaning of a charge of wrongdoing, as well as a call for the recipient of said charge to account for their actions.

An accusation – even when the allegation is false – can instantly raise your defenses and alert your body that danger is present. That’s the power of an accusation.

Sometimes the response is noticeable – a palpable discomfort that is evidenced with a “deer-in-the-headlights” expression, a tensing of the jaw, or a crossing of the arms and legs. Perhaps the “accused” leans back, defensive and unsure as to what to do next. Next time, how about leaning in?

Example No. 1

You are a local politician who is confronted by an angry constituent at a town hall meeting.

She asks:

“Why did you spend $10 million to rebuild this park? Our community has so many other needs!”

Your Response:

“Our community does have a lot of other needs. But, each and every dollar we spent on this park was worth it. I’ll tell you why. More than 100,000 people visit that park each year. We invested the money to create a park that can sustain those numbers, while spending the least amount of dollars to do it the right way. That means we are not coming back in only a year or two and asking for more money for restorations that should have been done right the first time. It was the best bang for your bucks, because there will be more money to meet the additional needs that you and I both know are there.”

Example No. 2

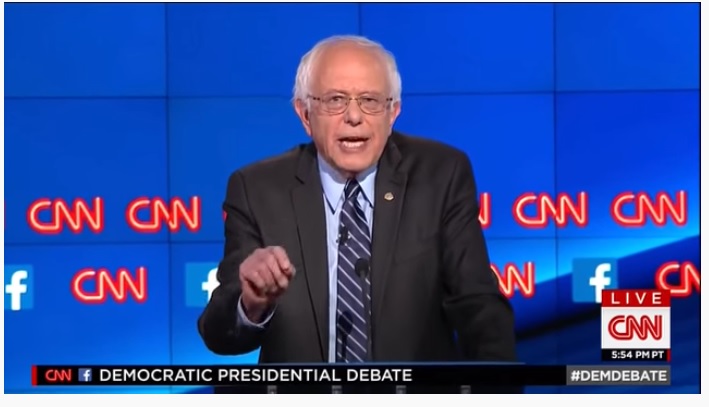

U.S. Rep. Bernie Sanders

During the Oct. 13, 2015 Democratic presidential primary debate that aired on CNN, candidate Bernie Sanders tackled moderator Anderson Cooper’s question about political labels by redefining assumptions, and reiterating and defending his positions.

COOPER: “Senator Sanders, a Gallup poll says half the country would not put a socialist in the White House. You call yourself a democratic socialist. How can any kind of socialist win a general election in the United States?”

SANDERS: “Well, we’re gonna win because first, we’re gonna explain what democratic socialism is. And what democratic socialism is about is saying that it is immoral and wrong that the top one-tenth of 1 percent in this country own almost 90 percent … as much wealth as the bottom 90 percent. That it is wrong, today, in a rigged economy, that 57 percent of all new income is going to the top 1 percent ….”

COOPER: “You don’t consider yourself a capitalist, though?”

SANDERS: “Do I consider myself part of the casino capitalist process by which so few have so much and so many have so little by which Wall Street’s greed and recklessness wrecked this economy? No, I don’t. I believe in a society where all people do well. Not just a handful of billionaires.”

Obviously, you can’t lean into every accusation. When accused of a crime, severe malfeasance, or a grievous comment, for instance, this strategy would work badly. It’s most effective, for instance, in addressing a pointed critique of policy, an unpopular decision, an inference of ineptitude or willful disregard, or a charge brought on by misinformation.

Deployed at the right times, this technique can help you eliminate defensiveness, clear misconceptions, and communicate a sense of utter confidence to your audiences.

10. How to Navigate the No-Go Zone

What two words can say so much and yet so little?

“No comment.”

Uttered by spokespersons who are legitimately bound to keep their answer under wraps, those two words often have the effect of leading the audience to think they have something to hide, or are guilty of something, even if their refusal to answer has nothing to do with guilt or innocence.

There are a number of no-go zones that require discretion. They include:

- Confidential employee or patient information

- Pending litigation or regulatory action

- Proprietary information

- Injury or death

- Ongoing negotiations

These may be no-go zones for you, but not for journalists. Given you will inevitably face questions about topics and issues that must remain out of the public domain, you need to develop a response for how you might say “no comment” without actually saying it, which is also known as the fine art of “commenting without commenting.”

It’s a tool that not only better protects the information, but also enhances your credibility all at once.

Here are some ways you can do that:

Example No. 1

You are the spokesperson for a city transit system. There has been a major accident involving a city bus, dozens of pedestrians, and other motorists. You know there are many injuries, several of which are critical. You have been asked to keep that information quiet until more information is known. During a conference call with several reporters, they bring up social media accounts of injuries and ask you to confirm the number.

Here’s how you might comment without commenting:

“We are seeing those same accounts. As much as I would like to provide more information about the situation, we are waiting until we get confirmation and more details from the emergency responders who are now on the scene. This is a tense and fearful situation for those currently involved in the accident and their families. We do not want to make it a more stressful situation by releasing inaccurate information.”

Of course, you must make good on your promise to follow up with any information.

Example No. 2

You are an economist who is working for a company that is in the news for failing to meet regulatory deadlines. A reporter is interviewing you about the overall global financial picture.

The reporter asks you:

“Can you tell me what will happen now that you have failed to meet the compliance deadline? What penalties do you face?”

Here’s how you might offer a “no comment” comment:

“As an economist, I have my eyes on the global market and what financial trends mean for our clients. I’m not privy to larger bank operations, so it would be inappropriate for me to comment on that.”

Example No. 3

Say you are the CEO of a private company that makes medical devices who is being interviewed on a business news radio program. The subject of revenue comes up – an area for which you are typically tight-lipped. Here’s another way of saying “no comment.”

Radio host: “How much revenue did this new product earn for you this year?”

Your response: “As a private company, we’ve made the decision not to disclose sales figures, because we don’t want to give our competitors useful information about how well our various product lines are selling. That said, I can tell you that we’ve been very pleased with customer response, and we’re ahead of our projections for that product.”

Building Your Media Tool Box: Part Two

The right tool for the job – it’s a simple mantra that can help with the most complex of situations. You now have 10 advanced media interviewing training tips (including Part One) you can use as tools to help you navigate everything from a misleading question to the need to be discreet. With practice, you will become an expert builder of effective, meaningful, and authentic media responses to whatever situation you face.

The right tool for the job – it’s a simple mantra that can help with the most complex of situations. You now have 10 advanced media interviewing training tips (including Part One) you can use as tools to help you navigate everything from a misleading question to the need to be discreet. With practice, you will become an expert builder of effective, meaningful, and authentic media responses to whatever situation you face.

See you next month!