Media Training Report 3: Six Ways to Be a Better Storyteller in Media Time

“The last man on Earth sat alone in a room. There was a knock on the door …”

What happens?

We certainly don’t want to ruin the ending. What we can say is that the late American author Frederic Brown used this two-sentence story to launch his 1948 short story, “Knock.” This tale within a tale shows that a great story doesn’t require tens of thousands of words. Although those two sentences are fiction (We hope!), they contain elements that can be just as effective in real-life tales.

As a media spokesperson, interview guest, or subject matter expert, you can employ equally effective stories to reinforce your messages. Telling stories in time-constrained “media” time, however, is not always so easy. To work, your anecdotes must be catchy, concise, and compelling. There’s one more “c” – they need to connect with the audience.

Tall order? Yes. Impossible? No.

Becoming a better media storyteller requires a firm grasp of the fundamentals and an ability to tailor your anecdotes to meet the distinct needs of your media interview.

We offer six ways to be a better storyteller in media time.

6 Ways to Tell a Great Media Story

1. Start with a Strong Foundation

Stories catch the attention of your audience because stories are a familiar framework through which we have interpreted and remembered new information throughout our lives. Recognizable storylines and themes help us to give order and meaning to new experiences and newly acquired knowledge.

Annette Simmons, the author of The Story Factor, explains the effect of such familiar elements on the recipient of your story. She notes:

“Story is like mental software that you supply so your listener can run it again later using new input specific to the situation …. Once installed, a good story replays itself and continues to process new experience through a filter, channeling future experiences toward the perceptions and choices you desire.”

While traditional narrative arcs, including the more enduring ones such as “Rags to Riches,” the “Cinderella” story, and the “Quest,” are more typically associated with fiction, they also can serve as a strong foundation for your media story. They turn slices-of-life stories, based on real people and real events, into compelling and catchy tales. You just need to know how to best lay out the details. You start by building a strong foundation.

Basic building blocks

There are some fundamental elements that you can stack together to make your story more compelling:

Plot – Just as you plot out a trip with different stops, you plot out your story with a collection of individual events.

Theme – This is the direction in which you are headed, and want to bring the audience along with you. This is the main concept you want to leave them with (“Love conquers all”). The way you sequence your plot points gets to the heart of your theme.

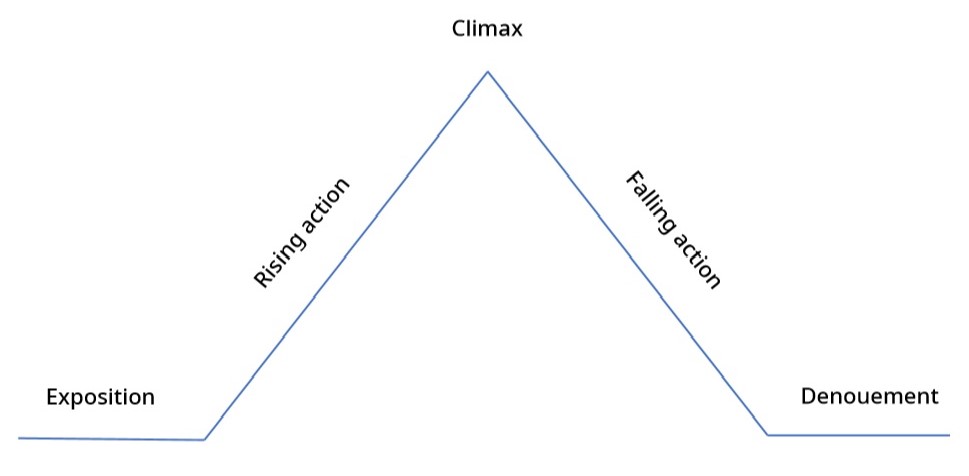

Narrative arc – This is the route your story follows, and there is nothing meandering about it. This five-stage structure – exposition (setting the scene), rising action, climax, falling action, and the denouement or resolution, gives the story its beginning, middle, and end. As the main character moves along this route, they meet with tension and conflict, which leads to further tribulations or triumph – or, at the very least, resolution.

Here’s an example:

You are an investment advisor turned entrepreneur who has launched a new digital platform that targets women investors. During a media interview, you are asked why you created the resource. Your main message might be:

“Women investors face different challenges than men. They often make less over their lifetime, live longer, and often move in and out of the job market, which can affect 401ks and other retirement options. I wanted a platform that would address those issues and provide practical knowledge as to how to get the most out of the money they were making and saving.”

That strong message can be reinforced by adding more concrete detail in story form:

“Imagine that you are a single mom who has been working for years at a job that doesn’t pay all that much nor offer much hope of promotion. You have a 10-year-old daughter and 12-year-old son. You struggle, knowing every day you are a crisis away from financial catastrophe. And then, ironically, your actual roof caves in. You are facing thousands of dollars in repair. You have no 401k, no savings, no investments. You tap your credit cards and dig the hole deeper. You are depressed about the present and panicked for the future. Your kids feel the stress. I know that woman. She was my mother. She was the inspiration for the platform, but there are millions like her out there, and that’s who we designed this platform for.”

Why this works

You have a plot, a theme (“Building for the future takes a plan and the proper resources.”), and it follows the narrative arc. It’s a common story that speaks to universal experience and fears. As you can see, you also don’t need to load up on characters or subplots. Small, simple stories can be as effective in making a connection with your audience.

2. Tap Your Audience’s Emotions

Here’s a simple formula to remember:

Strong characters + tension, surprise, conflict, or suspense = Engaged audience

If your story is driven by memorable and relatable characters who are facing adversity or attempting to unlock a mystery, you can bet you will reel in your audience because you hooked them where it matters – their emotions. Once caught, we become engaged in the story and, in a sense, are transported into the story.

Scientist and author Dr. Paul J. Zak, who has long studied the neuroscience of human connection as well as the power of storytelling to change attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, found that, in some instances, this narrative immersion can cause people to act.

This may have happened to you. You hear a story on the news about a family who has lost everything in a major house fire. A family spokesperson is interviewed and shares just how much the family lost. You imagine what it would be like to be without all the familiar comforts and a roof over your head. When the news station offers a website for donations, you log on and contribute funds to help the family get back on their feet.

When we care, we become interested. When we are interested, we pay attention. When we pay attention, we remember. When we remember, we can recall your message well beyond the actual telling of your story.

Create relatable characters in familiar situations who are experiencing universal emotions and struggles. Not every story has to be a tearjerker. Delight and surprise are powerful emotions, too, as we tend to pay attention and remember when the outcome is unexpected or a story challenges our perceptions.

Say you are a chief executive of a new website and app that allows consumers to compare prescription prices. A television news reporter asks you about the market you hope to reach. You want the audience to know that anybody can use it. You share a personal story:

“We wanted to design an app that anyone could navigate with ease. So, we did our beta-testing with an unusual group – my elderly father and his six closest friends, who are all less-than-tech savvy. We called it the ‘DT,’ or the “dad test.” Let me tell you, this was a cranky group that didn’t hesitate to let us know when we were on the wrong track. Finally, with the help of their candid feedback, we got it right – and even my father admits that now, largely as a result of his efforts, anyone can use this.”

Why this works

It can be challenging to make something as dry as target markets interesting. This response not only answers that question but also puts a story behind it. Your viewers may remember this: “Even his cranky father could use it!”

3. Tell It Like It Is

Vivid details, descriptive words, everyday examples, and concrete illustrations, (as opposed to abstract concepts) will help your audience to picture the people, places, and objects that are populating your stories. When it comes to memory retrieval, a growing body of research has found that visual cues help us to better retrieve and remember information. Not only that, researchers have found our ability to see, store, and then recall images largely trumps our ability to do the same with words.

The imagination of your listeners and readers, then, is a powerful tool that paints pictures in their minds, which ultimately can affect their recollections, actions, and opinions.

Here’s an example:

Say you are the spokesperson for a utility company, and you are alerting the public to the damage and cleanup following a series of powerful late-night storms. You want to convey that the company is doing its best, but that the damage is far-reaching. If you paint a clear scene of what you and your crews are seeing, you transport your audience to the scene and give meaningful context as to why this is going to take some time.

You could say this:

“The storm knocked down many trees and limbs onto roads and houses. To be clear, we know this is going to be a challenge. But we have employed our front-line crews to pave the way for our technicians to get the electricity up and running.”

This example, however, provides more illustration, and a better picture of what the crews are up against.

“I’ve seen the devastation, and it’s like a giant walked through here last night. There are hundreds of broken and toppled trees, cracked limbs, and utility poles snapped like toothpicks. That makes travel and recovery extremely difficult. We know people are suffering and want to get back to normal. So, we have called in the reinforcements. Hard-working cleanup crews will soon be arriving from around the region. Throughout the next two days, they will slice their way through roads large and small, working from morning until night, to allow residents to get the electricity flowing again.”

Why this works

Both examples are filled with facts and information. However, the second example puts the reader or listener directly into the scene. Once “transported,” it’s easier for the audience to empathize with the cleanup crew and “see” that they are doing their best in a difficult situation.

4. Pick the Right Story for Your Audience

When does a book gain its power? When someone opens it.

When does a story take hold? When people start telling it.

An audience is crucial to storytelling. The very word itself implies it. A story is told. An author needs an audience, otherwise; she’s just talking to herself.

Frederic Brown’s fictional short works because it speaks to universal concerns. Brown wanted us to keep reading, so he spoke to common fears – being alone and not knowing what comes next. That made his story compelling, all in a catchy and concise way. In real life, the same dynamic is true. Your audience’s concerns drive their interests. If you know your audience’s needs, then you can align your message to what matters most to them.

Having done your work to establish your message and align it to the issues and values that are of concern to your audience, it’s time to team that message with the right story. Most messages seek to inform, to get people to act, to urge them to change their minds, or to tout the benefits of a concept or object. Your story should not only point your audience toward your message but also what you want them to do.

Here’s one way you can do that:

Let’s say you want to shift the perspective of your audience. A story that reveals an “a-ha” event could effectively do the trick. The arc should move from an old way of thinking to a new insight, based on a pivotal moment that brought about the understanding. So, say you are a spokesperson for a relief organization, and you are being interviewed about what is needed to help a community devastated by a recent storm. Your audience is interested in helping, but you want to guide them toward cash contributions, rather than material donations.

Here’s your story:

“Several years ago, I was with a group of volunteers in a trailer picking and sorting our way through a huge pile of blankets and clothes. These jobs usually took hours. And there were a half-dozen more piles in nearby trailers. But then, a volunteer asked, “Why are we stuck in a trailer, when we should be out there finding out what people really need?” She was right! The donations, while well intentioned, were costing us in time, volunteer resources, and expenses. Moving the containers to recovery sites cost more than buying supplies. I realized that day, if you want to donate, cold, hard cash makes a far better investment.”

Here’s another way:

Say you want to sell an idea or product. Pick a story that reveals the benefit. The easiest way to do that is to put the audience in your shoes by providing a personal account of how this has made your life better. Let’s return to that new app and website that allows consumers to compare prescription prices. This time the question is about why you were inspired to launch it. A personal story can reveal the why, as well as how, that app will make your audience’s lives better.

Here’s your story:

“Learning that I had rheumatoid arthritis was bad enough, but discovering the cost of the remedy was worse. Three-thousand dollars a month! I managed for a while, but ultimately I couldn’t do it. I lost my house, filed for bankruptcy, and moved in with my parents. The soaring cost of prescription drugs is financially killing hundreds of thousands of people like me. I needed to do something about it, so I created BetterPill.com. You can find discounts, comparison pricing, and ways to work with your insurance. It’s everything I’ve used to get back on the medicine and knock my cost down to $600 a month. It is not a cure, but I hope it helps others avoid what I went through.”

Why these work

Both stories reinforce the message they are trying to convey. In the first instance, it’s all about self-revelation, which might help you change someone’s behavior. The second story reveals how the service benefited one person, and leads to the expectation that it can help others, too.

5. Mix It Up

Novels can range from a quick read to a 700-page tome. Stories can be long or short. They can be told in the first person or through an observer. Some stories are realistic, while others are fantasy. Some stories predict the future, while others delve into the past.

You will want to build a collection of anecdotes that vary in length, narrative point of view, and structure so that you can pick and choose depending on your needs. It’s your own personal library of media stories.

Vary the length

Not all stories need to be epics. Sometimes, all you need is 30 seconds.

For several years, the NewYork-Presbyterian healthcare system has presented its “Amazing Things” campaign, which features 30- and 60-second spots of patients sharing their stories of survival and life-changing procedures. Through the patients’ own words, the message comes out loud and clear – NewYork-Presbyterian is doing groundbreaking work that is leading to transformational change in their lives.

Here’s just one:

Vary the main character

You don’t always have to be the hero of your tales, nor should you be. No matter how descriptive or interesting the stories, too much you gets old real fast. Where to look for compelling protagonists? Here are some ideas:

- Share a story of how a client benefited from your service

- Recount a tale of an employee going above and beyond

- Share why a member of your team was motivated to develop a new product

- Present a challenging problem through the eyes of someone who is experiencing it

Vary the pattern

If you follow the same plot for every story, the audience may tune out. Your theme can stay the same, but the plot needs to change.

Say you are that spokesperson from that relief organization. You want to reiterate this main message: Our work can only be done with help from the public. It’s easy to take a one-note approach with multiple stories of volunteers saving the day, but if you dig deeper, you can find other stories that carry a similar theme but tell a different tale.

Here are some alternative storylines:

- Story No. 1 is about a volunteer who overcame difficulties of her own to make it to the scene where her presence was invaluable.

- Story No. 2 focuses on how an exchange with a volunteer renews one client’s faith in humankind.

- Story No. 3 spotlights a longtime volunteer who works to pass her institutional knowledge on to younger volunteers.

Why these work

We like variety, which means a one-note storyteller stands the risk of becoming background noise.

6. Know When to Go Long, When to Go Short

You’ve come up with some great stories, but you must consider where they are being told. Story length matters, so tailor your story to the medium. It’s all a degree of how quickly you go straight for the bull’s-eye.

Short stories: If you are being interviewed by a non-live cable news program that will only use a few edited clips, you might have to condense your story to 10-15 seconds. It’s best to skip unnecessary details and get to the heart of your story.

Medium-length stories: If you are being interviewed during a live five-minute radio or television segment, or for a longer print piece, you can share somewhat longer anecdotes that are richer in detail.

Longer stories: Perhaps you’ve been booked on a 60-minute podcast or a 20-minute radio talk show, or are the focus of a lengthy feature story. Your stories have some room to breathe and be filled with details that provide even greater context. Still, make sure the stories support your main points. One more tip: Utilize stories that might prompt questions and allow the host to jump in or follow up. (You: “That’s when I discovered there was more to learn.” Host: “So what did you learn?”)

Why it works

A 12-second clip on a cable news program will require a different approach than a 60-minute podcast interview. If you arrive with long, drawn-out stories for the former, you run the risk of failing to land your message in time. If you present short stories with few details during the latter, you may not be asked back.

What Stories Will You Tell?

Your stories do not have to be epics. Often, small slices of life are the best way to convey what it is you are trying to say. When you start with a good story and employ the elements and details that make it a great story, it becomes an effective vehicle for your message, whether you seek to inspire, inform, or encourage action.

As Annette Simmons says:

“(A) story doesn’t tell people what to do but it can powerfully influence what they think about as they make their own choices.”

Now, it’s time for you to go tell your story.