Episode 3 | National Museum of African American History and Culture June 27, 2021

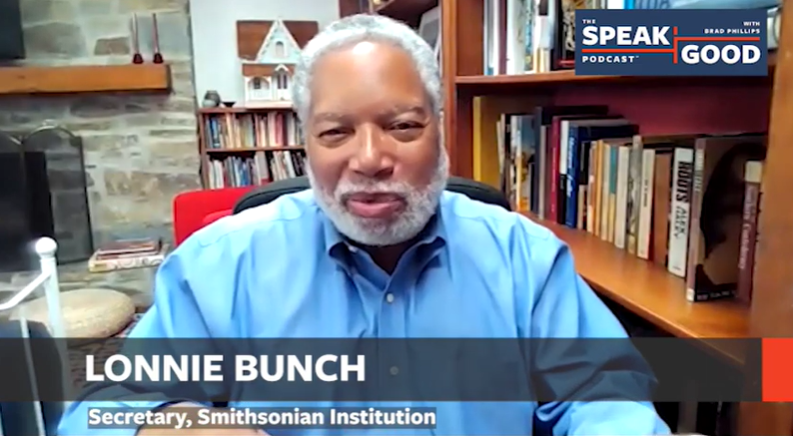

GUEST: Lonnie Bunch, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution

As the founding director of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Lonnie Bunch was responsible for creating a museum that started with no objects, no staff, no building – not even a location for the building. Since opening in September 2016, the museum has welcomed 6 million visitors. In this episode, he discusses how he created a space that tells stories of tragedy and triumph, hardship and resilience. We’ll also discuss several timely issues related to race in America and his still acute imposter syndrome.

GUEST BIO:

Lonnie Bunch is the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, the first African American and first historian to serve in that role. Prior to becoming Secretary, Lonnie was the founding director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Considered one of the most influential museum professionals of his time, Lonnie has also worked with the California African American Museum in Los Angeles, National Museum of American History, and the Chicago Historical Society. His latest book, A Fool’s Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the Age of Bush, Obama, and Trump, chronicles the making of the museum.

LINKS:

The National Museum of African American History and Culture

Former President Obama’s speech at the opening

Former President George W. Bush’s remarks at the opening

“Our Shared Future: Reckoning with our Racial Past”

Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom by David Blight

Full Transcript

BRAD PHILLIPS, HOST, THE SPEAK GOOD PODCAST:

One of our clients is a successful executive with one the world’s top-ranked transportation companies. He’s a true professional – unfailingly polite, relentlessly thoughtful, and deeply committed to his work.

Shortly after George Floyd’s murder at the hands of a police officer in the spring of 2020, we spoke on the phone, and our work-related conversation shifted to the horrific event that had just occurred on the streets of Minneapolis.

What he told me during our call has stuck with me ever since. My client – a tall, good-looking, middle-aged African American man who lives in New York City – shared with me just how much race influences his daily activities.

Every time before he leaves his home, he told me, he considers what he’s wearing and whether it could attract the wrong kind of attention.

When he approaches people on the sidewalk, he smiles to let them know he isn’t a threat.

If he speaks to someone shorter than he is, he shrinks his frame to come across as less intimidating.

Now, I’m not totally naïve about race in America. I know that many Black families give their children and teenagers “the talk,” in which they warn their kids about risks related to racism and law enforcement. I know that African Americans are more likely to be stopped by police, punished when they are, and incarcerated for longer periods of time. I know that many Black job applicants face steeper odds for getting the job they want if they have a – quote – Black-sounding name. But I had never thought about the daily rituals that this man, my client, has to endure – and how a baseline level of fear and anxiety associated with race regularly accompanies his choices. That there was no amount of success or achievement that would make him feel safe enough to set his self-protectiveness aside.

That conversation exposed a gap in my knowledge and made clear to me that I had a lot more to learn about race in America.

I ordered books – about anti-racism and caste and reconstruction – from Black-owned bookstores.

I followed more Black voices on Twitter so I could learn from their lived experience and share their voices with others.

And it helped cinch my thinking about what this podcast would become: A forum to discuss these issues – hopefully thoughtfully – with a candid admission of my own blind spots but with the aim of becoming a meaningful, if small, part of the solution.

And, as I did read and learn more about African American history, I kept thinking the same thought: “I didn’t know.”

One book, by Pulitzer-Prize winning historian Alan Taylor, provided one particularly harrowing excerpt that left me absolutely stunned. It was about the “Middle Passage” – the journey enslaved people endured as they were transported from the West African coast to their new, brutal lives in North America. In American Colonies, Taylor wrote:

“On most ships, the slaves were jammed into dark holds and onto wooden shelves that barely allowed room to turn over. At six feet long by sixteen inches wide and about thirty inches high, the standard space for a slave was half that allowed to transported convicts. Lacking clothes and bedding, the slaves slept on their rough wooden shelves and in the wastes that their bodies produced overnight. A captain later recalled, ‘The poor creatures, thus cramped, are likewise in irons for the most part which makes it difficult for them to turn or move or attempt to rise or to lie down without hurting themselves or each other. Every morning…more instances than one are found of the living and dead fastened together.”

I didn’t know. I had learned about the slave trade, of course, but had never read such a vivid description of just how inhumane the conditions were aboard those ships.

I didn’t know about Private Edward Green, a 23-year-old Black soldier who boarded a city bus in Alexandria, Louisiana in 1944 – and who was killed by the white bus driver after Green – who had served in the military for his country – refused to sit in the segregated section. The bus driver faced no punishment.

I didn’t know the details of the Tulsa race massacre that killed as many as 300 people, most of them Black, until the 100th anniversary of the event was commemorated in May 2021.

How did I never know those things? I attended a good public school, took history classes in college, and am an intellectually curious lifelong learner. I could blame incomplete school curricula – and there’s something to that – but ultimately, the knowledge is out there for anyone interested enough to seek it.

Today’s episode is about one of the greatest spaces in the world to learn more. The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, which opened in 2016, sits on the National Mall, near the Washington Monument, on a 5-acre site that was once part of an 800-acre tobacco plantation, on which 245 Africans were once enslaved.

Putting that museum together wasn’t easy. It started with no objects, no staff, no building – not even a location for the building. But our guest today found a way out of no way. When hired as the founding director of the museum in 2005, Lonnie Bunch – a historian who once led the Chicago Historical Society – charted a course that led to the museum’s successful opening just 11 years later.

During those 11 years, Mr. Bunch led the collections effort that helped the museum secure everything from ankle shackles used during the Middle Passage and a South Carolina slave cabin to Muhammad Ali’s headgear and Chuck Berry’s famous red Cadillac.

But before collecting thousands of objects, Bunch had to establish the museum’s tone. He wanted to tell the “unvarnished truth,” but didn’t want to focus solely on hardship. He wanted to make it an inviting space for visitors of every race but didn’t want to whitewash history.

On the day the National Museum of African American History and Culture opened to the public, former President George W. Bush, who signed the legislation authorizing the museum’s creation, said this to a crowd of thousands:

(GEORGE W. BUSH SOUNDBITE)

“A great nation does not hide its history. It faces its flaws and corrects them. This museum tells the truth that a country founded on the promise of liberty held millions in chains. That the price of our union was America’s original sin.”

(END OF SOUNDBITE)

In the end, Bunch and his team created a space that expertly balances stories of tragedy and struggle with stories of triumph and resilience. He details his 11-year journey in his excellent book, “A Fool’s Errand: Creating the National Museum of African American History and Culture in the Age of Bush, Obama, and Trump.”

His story, though, doesn’t end there. In June 2019, Lonnie Bunch became the 14th Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, the world’s largest museum, education, and research complex. In that role, he leads all 19 Smithsonian Museums, several research centers, a robust digital presence, and more. And, in so doing, he became the first African American and first historian to lead the Institution.

First of all, I do want to tell you, I read your book, which I thought was terrific.

LONNIE BUNCH:

Oh, thank you.

PHILLIPS:

You were candid and direct in places that in most memoirs of that sort, I don’t often see. You stopped short in some cases of naming names, which was (inaudible) …

BUNCH:

(LAUGHS)

PHILLIPS:

But I was surprised by your candor.

BUNCH:

You know, I’m a historian. The key is tell that as John Hope Franklin always said, we tell the unvarnished truth.

PHILLIPS:

I know it, I know it. And before every episode I select – I collect vinyl records – and before every episode I select a record that makes sense for the person I’m speaking with. I don’t know if you can see over my shoulder.

BUNCH:

Yes. I can. Sam Cooke.

PHILLIPS:

A change is going to come, that was your music at opening.

BUNCH:

Yep.

PHILLIPS:

I think for very obvious reasons, but I’m curious from your perspective, why out of every song you could have selected, that was the one you went with.

BUNCH:

I think the great strength of the nation is its ability to change. And I think part of the way you change is by understanding yourself through history. And I wanted the museum to be a place that would not be about guilt. It would be a place that would help people find understanding, context, prod them to change. But in essence, the key is that a change has happened in my life in terms of fairness, but there’s still a long struggle ahead. And so, change is going to come was my way of saying, we’re not at the promised land yet. We’ve got a lot of work to do, but we’re moving in that direction.

PHILLIPS:

I’ve heard you talk so many times about, you don’t want the museum to be a place, or you didn’t want the National Museum of African American History and Culture to be only a museum of pain and tragedy. You also wanted it to be about resilience and strength. And it seems to me that song captures both of those things beautifully.

BUNCH:

Absolutely. And plus, Sam Cooke is one of the greatest artists who unfortunately died so early. I wanted more people to know who he was as well.

PHILLIPS:

And I love Otis Redding and Aretha Franklin. You will never hear me say a bad word about either of them. And they both did versions of that track.

BUNCH:

That’s right. They did.

PHILLIPS:

Although, for my money, nobody can touch the Sam Cooke original.

BUNCH:

None.

PHILLIPS:

It is so moving. I met you for the first time in 2005, shortly after you were named the founding director of the museum. And I was brought in ostensibly to work with you on media training. After our session together, I walked out of there and I said to our friend, our shared contact, I don’t know if I did anything. You were fully formed before you walked in the room. If I did one-tenth of one percent of anything in that session, that would be a big compliment. But then when I read your book, it was striking to me how you said that you’re very private and you didn’t know if you could handle the media scrutiny. And so that was interesting to me because there was a disconnect between the talent that you very clearly have and the feeling you had about having to do that. I’m curious if you feel like you’ve grown into that, if you’re more comfortable in that role as a public spokesperson now.

BUNCH:

I always felt, I knew how to work with the media. Understood, you know, what to say, what not to say, how to be nimble. But, what I was really getting at is that basically I’m really a shy, private person. And so that every time I had to say to myself, okay, let’s control your nerves. Let’s figure out how to do this. In essence, I always drew from, as I mentioned in my book, the fact that in ninth grade, I had to make a presentation that ended up talking about race to a group where I was the only Black person. And I thought that was the worst public speaking moment of my career. And so every time I then would give another talk or work with the media, I’d remember that speech went well, that talk went well. And if I could do that in ninth grade, I could handle anything else.

PHILLIPS:

That’s right. You also talk in the book about growing up black in an overwhelmingly white community of Bellville, New Jersey. And I wondered if that experience created these qualities in you of learning how to navigate the world, and if it even influenced your communications style in having to speak to so many audiences through the years.

BUNCH:

Absolutely. I think growing up in that town forced me to realize a couple of things, that if I was going to survive, that I had to figure out ways to straddle many worlds. I also had to learn how to listen carefully and analyze what was going on because there was sometime physical danger. It really gave me so many skills. It taught me to be clear, but it also taught me to realize that the most important thing for me was to accomplish what I needed to accomplish. And if that meant it was somebody else’s idea, that’s fine. And so, it really taught me to be flexible in order to convey what I wanted. But what it really, more than anything else, what it taught me was that you carry an extra burden, that you don’t get a chance to not understand how to read a room, not understand how to sort of pivot. So it really did force me, partly out of survival, but it really did force me to learn how to be flexible, protect myself, but still try to accomplish what I needed to.

PHILLIPS:

You wrote about that, I thought, quite movingly in your book. You talked about needing to read the racial subtext in a room. And you said that you needed to learn how to control your anger and find ways sometimes with subtlety, occasionally with righteous indignation, to overcome the notions of white privilege that shape many of those sessions. And so just based on what you just said, I can’t imagine because of that privilege, what it is to walk into a room, having to think of two things, what do I need to do to be successful in this meeting? And how do I read and adjust myself to the unspoken subtext in the room? Is there a lesson you’ve learned that makes it easier for you to read that subtext?

BUNCH:

I would argue that’s the cost of doing business, right? So, it really wasn’t something where I could say, I wish I didn’t have to do that. It was basically, to me, just like breathing, you had to do it in order to survive. And so, the lesson I learned was really to remember to have confidence in my ability of what I want to say and what I want to accomplish. But recognize that I’ve got to figure out how to make it work at that moment. I would argue what it does for many people, African Americans, many women, they find ways to quickly understand the context they’re in. And, they find ways, sometimes very directly, sometimes subtly, to navigate that and get to where they need to be. Is it fair? No, but it’s life in the big city. And so, for me, I just have to accept that as part of the cost of being Black in America.

PHILLIPS:

And I have to admit, I have a discomfort because most of the questions that I wanted to talk to you about today are centered on matters of race. You are, of course, now the secretary of the Smithsonian, and, in that role, you oversee 19 museums, only one of which is the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

BUNCH:

But that’s still pretty special. (LAUGHS)

PHILLIPS:

I was just saying to our producer, before we jumped on that, it is a gem. My God, do I love that space you’ve created, but I do feel funny speaking to you about race, given that your role is so much more expansive now. If the director of one of the other 18 Smithsonian museums had become the Smithsonian secretary, I’m not sure I would be talking about modern art with them. Should I feel funny about that?

BUNCH:

I think that what you do is you talk about what are some of the skills that the person you’re talking to and race has always shaped what I do. It doesn’t limit what I do. It doesn’t mean that I can’t talk about abstract expressionism in art. It doesn’t mean that I can’t revel in discussions around climate change or sustainability, but it just means that in essence, that’s part of the platform who I am, and that I will always see things, I will always hear the sound of race in my ear. But it doesn’t mean I always listen to it. Doesn’t mean that I always articulate it. But I always hear it in my ear.

PHILLIPS:

There was a paraphrase in your book. You were paraphrasing Thomas Jefferson. I had never heard this line that you use this quote of saying that talking about race is like holding a wolf by the ear. So, you were in that very complex role of trying to create a space that told the African American story through the American lens, but that didn’t alienate people, who might not have typically exposed themselves. Let me, uh, grossly over-generalize here. Let’s take an archconservative, someone who is upset about things like critical race theory, who’s not your typical demographic that you would think would be open to some of these stories. How did you think about reaching that person when he went into the gallery?

BUNCH:

Well, I think first of all, you had an amazing opportunity because it’s the Smithsonian, right? That there are many people who will grapple with issues as they come to the Smithsonian, go to the Smithsonian online, that they won’t in Chicago, New York, or L.A. So, one, I already had that foundation. There are going to be people who are going to grapple with this because they’re doing the Smithsonian. But I also thought about, very candidly, how do we do this? I talked to educational psychologists. I talked to futurists. I talked to educators. I talked to people whose politics were very different than mine. And what I realized is that one of the great things we needed to do in this museum was yes, tell the unvarnished truth because I had faith in people’s ability to grapple with that truth. But, we had to reduce it to human scale. We had to not be talking about critical race theory. We had to talk about an individual’s family or decisions they’ve made. And so, throughout the museum, you will see there was a conscious effort to – by the imagery we use, by the wording we use – to really humanize this. And my belief was that when you humanize something, instead of talking about slavery, look at slavery through the life of a particular family living in one cabin. Everybody can engage in that, can find meaning. Can we get everybody to say amen? No, but I think in many ways, the way we did it gave people an opportunity to see themselves, regardless of who they were in these stories.

PHILLIPS:

That really struck me. You used a phrase that I’ve never heard before, and I love it, uh, peopling the past. And that idea that these big issues, whether it’s slavery or Antifa or critical race theory or any of these sorts, they’re big and abstract, and everybody brings their own meaning to those terms. But when you tell that story of an individual, it’s harder, I guess, to dispute the facts because it’s that person’s lived experience. But I guess it’s also a softer way of sharing the larger story.

BUNCH:

I think so. You can approach the big issues from a variety of ways. You can approach from up here, and there are times you really need to do that, but I wanted people not to walk through a museum and say up, check it off. I wanted them to be emotional, to care, to find connections. And that I felt that if we could allow people to see parts of a story in a human scale, then almost everybody can say, I understand about migration. My family immigrated from Italy. I so just ways to give people opportunities to make connections.

PHILLIPS:

Is it important to you … I’m thinking about some of the issues, like, let’s say, policing in America and you have these – and I don’t want to overstate it because I know there’s a lot between the extremes – but on one side you might have Blue Lives Matter. And on the other side, you might have Black Lives Matter or defund the police. Is it important or necessary for a museum to make sure that each visitor hears their perspective represented?

BUNCH:

You know, I’ll be really clear. You want to have as many perspectives as possible, but what you really want to do is to provide context. So people understand what the issue is. And hopefully by giving them that context, by giving them more data, they can come to a decision. They may not come to the decision that I may want, but they’re going to come away educated. And maybe as John Hope Franklin used to say to me, what you want more than anything else is somebody coming through the museum and be changed. They may not go from the right to the left, but to be changed, to be open to new ways of looking at things. And I think that’s a major contribution that we want to do.

PHILLIPS:

When you look at the people retreating to their factions, their political factions, it seems that people are less open to some ideas than they used to be. First of all, I’m curious, in your experience do you find that to be true. And beyond peopling the past, maybe even on an individual lesson for listeners, if we’re sitting around that Thanksgiving table, having issues around 1619 versus 1776, or any of these other things that might be in the news at that moment, what else have you learned about how to keep people open in these conversations, so they don’t immediately retreat to their factions.

BUNCH:

In conversation it’s really about listening, right? But it’s also about making sure people understand the accurate truths, through scholarship, through research. So I always start there, that’s the engine of where we go. Here’s what history tells us. But I find myself in many conversations, explaining people how history evolves, how interpretations change, how new information changes the way we think about the past. So, in some ways, part of the challenge is to help people understand that what we’re doing is we’re experimenting to understand who we are as a nation. And sometimes that experiment will push us in certain directions. But the goal here is ultimately to provide context and understanding. And as I always say, my job as a historian ultimately is to define reality and give hope.

PHILLIPS:

I love that. Define reality and give hope. How are you doing that with your new initiative? I believe you announced this earlier this month. It’s called “Our Shared Future: Reckoning with our Racial Past.” Can you talk about that? And what you see as the role of cultural institutions like the Smithsonian?

BUNCH:

At a time when a nation is in crisis, we’ve been in crisis over the pandemic, over issues of race, I think institutions, especially cultural institutions, have a role to play. They’re trusted. They are places where people of different points of view actually come together and interact. So, I think that there’s a responsibility to help. Ultimately, I would argue the goal of any cultural institution, regardless of whether it’s large or small, is to make their community, make their country better in modest ways or in large ways. For me, crafting “Our Shared Future: Reckoning with Our Racial Past” is really the emphasis is a two bounce. One bounce is our shared future. How do we as a nation become to a shared future? A future that is better. A future that is fair. A future that allows us to live up to our stated ideals.

And what I wanted to do was to use the Smithsonian’s ability, first of all, to draw from our own expertise – scholars on Latino issues, native American issues, African American issues – so we have this resource that’s the Smithsonian, but also the Smithsonian can call anybody in the world to help us think about these issues or help the public grapple with these issues. And so, what this initiative is, it’s both, let’s look at this on a very high level. How do we bring conversations around difficult issues? And then how do we move to a kind of town hall meeting, either virtually or actually, that allows people in Minneapolis to contextualize what went on there, to understand how history shapes who they are. And maybe then by bringing people who have different points of view together can find some understanding. The goal here is to do what we can to help make a country better. I would argue that one of the greatest chasms in this country has always been about issues of race. And notice I’ve said this is about race, not just the African American experience. So, the goal here was to say that we want to help the country find the bridges that lead us to a better tomorrow.

PHILLIPS:

I’d like to shift to politics, and this is not a gotcha interview. But you were very candid about this in your book. And so, I wanted to ask about the visit (former) President Trump made to the National Museum of African American History and Culture shortly after his inauguration. You shared in the book, and by the way, this was reported on extensively at the time, but I was surprised in your telling of that story, in the book, that even behind closed doors, when he wasn’t doing it for shock value, he was saying a lot of the same things in making the visit about him.

BUNCH:

I think what I take away from that, candidly, is, first of all, the positive thing that he had interest to come to the museum. And I really think that a museum’s job is to educate. I think that was part of the educational experience that he had going through the museum. I think that it also reminded – it helped me a great deal – me to think about how do I make sure people who don’t think about these issues, who maybe don’t care about these issues, how can I make the connections? And so for me, it was an experience that was really in keeping with how I worked with George Bush, Barack Obama, I recognized I needed to work with that administration. So ultimately the visit gave me guidance on how I moved forward, working with them in the future.

PHILLIPS:

And the political fault lines that you have to be careful to avoid. I was struck that the then secretary and you co-bylined an op-ed in the Washington Post. This was shortly after Colin Kaepernick kneeled, and, and it caused a political furor. And I think it was a brave act for you to do that because I think we’ve seen in Washington over the past several years that it doesn’t take much for a leader to turn their followers against institutions that were previously trusted. How worried were you about that?

BUNCH:

Well, look, you have to be who you are. And, for me it’s about how do I help a country find fairness? How do I use the power of the word, the power of the past, not to say we are right, you are wrong. But to provide that understanding. So I’m not sure it was brave. I think it’s what you have to do. But I’m also smart enough to know that this is a political world. So, one of the things we did was when I came back to Washington was make sure I had allies on both sides of the aisle. To spend time on the hill when I didn’t need anything. To work with people who were Republicans or Democrats, who were independent. What I recognize is that you’re going to get beat up. And I think this is the key for me. You’re going to get beat up no matter what you do. So, you might as well get beat up for doing the right stuff. And have allies that will help you, but there’s no doubt that there are times you’re going to lose no matter who your allies are, because you’re in this political world. But I would argue that it’s not about bravery. I don’t think I’m very brave at all, but I think it’s about what do you risk to help a country? When you see a lack of information, provide that information. When you see people not understanding this long tradition of political change in protest, say that. Because I think that peaceful protest, peaceful protest is the highest form of patriotism. And so, I wanted to celebrate the Colin Kaepernicks. One of the things that moved me early in my career was doing an exhibition on history of Blacks in the Olympics and getting to know John Carlos and Tommie Smith, the people that gave the black power fist to the 1968 Olympics and to realize what they suffered, what lack of opportunities they had, what burdens they carried for the greater good. And I wanted people to recognize that change is not easy. It’s not without loss, but, my God, have there been heroes in the past that should inspire us to move forward today.

That is such a great example because it seems like every time these debates come up, Colin Kaepernick is now in the news, it lacks the context of, have you heard of Cassius Clay? Have you heard of Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey? Have you heard these stories? You being able to put that in that broader context, I think, makes your role essential. It helps us understand the current moment so much more.

BUNCH:

Well, let me give you the best example for me. When I thought about athletes and people saying athletes shouldn’t talk, I realized that they’re professional athletes for a limited part of their career, but they’re Americans for their whole life. Don’t Americans have that right to express themselves? So, to me, this was really a broader discussion, not about the role of athletics, but the role of Americans to be able to express concerns in positive ways.

PHILLIPS:

Yes. Now the name of this is The Speak Good Podcast. So, I want to ask a couple of questions about communications. I was struck first by your telling of the story, back in 2005, you come to the museum, you walk into the room for the first meeting with the museum’s council. Could you describe the people who are sitting around the table? How you responded to that? And the advice you got from the then secretary following that meeting?

BUNCH:

This was such a whirlwind. I mean, I’d said yes to the job, but I hadn’t planned on starting. But they said, oh, you got to come back a month earlier, at least to meet this board. And it was in the African art museum and African art you start upstairs and you work your way down. So, I am winding my way down and suddenly I get to this room and I look around, I said, oh my goodness, there’s Oprah Winfrey. There’s the head of time Warner, the head of American Express. There’s Bob Johnson created BET. I am terrified like, I’m this kid from Jersey, what the heck am I doing in this room? And so, you know, I, they asked me to give a little talk about my vision, about who I was. I think I probably did a lousy job. I was very nervous. And so, the next day, I met with the secretary of the Smithsonian, Larry Small, and he said, “Well, I could tell you were nervous.” And I said, “I was scared to death.” And I felt if I couldn’t handle this, oh my God, was this, the right job for me? And he said to me, you’ve got to remember that these people are at the top of their game, but so are you. You are as important in your field as they are in theirs. And most importantly, they want to get to where you want them to be. So, while that always gave me a little confidence, it always, when I was still scared whenever I talked to these people, I think that was really helpful to me to recognize that in some ways I was their equal, which is something that in my mind I wasn’t. But, I’ve been so fortunate being able to work with gifted people like that.

PHILLIPS:

And I am always struck, as somebody who has the privilege of working with a broad cross section of people in all walks of life, that feeling of imposterism doesn’t go away. And in some ways it even gets worse over time. Not better

BUNCH:

Oh, absolutely!

PHILLIPS:

The reason I wanted to ask you that question was, I think it’s relieving to other people to hear that this man who has accomplished so much still has that.

BUNCH:

I tell people all the time, when they ask me how I’m doing, I tell them, and I feel this truthfully, I tell them I’m still fooling everybody. So, I think we all have that, but I really do. I mean, I’m a kid from a small town who once thought the most important thing I could ever do is be a university professor and have classes of 10 or 15 kids. And suddenly I’m in this situation that I would never imagine I’d be in. And what I tell young kids is that it’s all about the evolution. It’s all about being willing to take risks, to recognize what you don’t know, and to challenge yourself, to learn that, and then to jump into the water. But hopefully make sure you had to swim before you jump into the deep end.

PHILLIPS:

I am curious, looking back to 2005, do you feel the same acute imposter syndrome that you did back then?

BUNCH:

Oh God, yes.

PHILLIPS:

You do?

BUNCH:

Oh, absolutely. I’m the secretary of the Smithsonian and it’s still hard for me to say that after two years. Right? So there is my greatest strength has always been my ability to confront fear. I’m not one of those people to say, oh, I’m always confident. I’m scared all the time, but my father taught me and my mother taught me that the success is confronting those fears, finding ways to get around them and using that fear to motivate you forward. So, for me, um, I will always say that I am terrified most times when I’m able to sort of control that, use that to fight the good fight.

PHILLIPS:

And, you as a leader must be aware that when people approach you now, your own staff, they probably have those same feelings about you that you did when you walked into the room with Oprah. How do you, I mean, I assume, and I know you a little bit, I assume you’re conscious of that and purposely do things to try to set them at ease.

BUNCH:

You know, for example, I rarely use the term secretary. People use it all the time. Just call me Lonnie. Because for me, even though there are some probably some chinks in the armor, I’ve always felt that my success, whether it’s at the Chicago Historical Society or building the African American Museum, it was building a sense of family. We’re in this together. We’re not all equal, but we’re all equally relevant and equally important. So I really try to convey that. Because what I want as a leader is people who will tell you the unvarnished truth, who will help you see – maybe I’ve seen too many old movies — but I wanna know what’s all along the waterfront so I can make the right decision. And you need good people to help you to illuminate all aspects of that, right?

PHILLIPS:

I’d like to end with a couple of perhaps lightening round questions, although you’re welcome to take as much time answering them as you’d like. The first one is, (and) Tulsa is a great example, that a lot of people, and I’m going to include myself in this (in that) I was aware of Tulsa, but, in May, when it was, I think the 100th anniversary, suddenly there was a lot of media coverage around that. And I learned a whole lot more about what happened in Tulsa – 300 people or so died, most of whom were African American – than I ever knew before. And it made me wonder what other stories don’t Americans know about that you think they should. Is there one that comes to mind that you think was a seminal event that is too frequently not taught or known?

BUNCH:

I can give you 175, but I think really let me do two. One is the creation of the NAACP in 1909. Because, people know the NAACP, but the fact that this was a multiracial organization from its inception, that it really suggested that one of the great strengths of America is when people cross racial lines to help a country live up to its stated ideals. To me, that’s one of those positive moments that I wish people knew more about. Because I would always argue that that was replicated when we opened the museum in September of 2016. And here you saw Republicans and Democrats, people across racial lines who came together for the greater good and look what you can accomplish. So, there’s that. And then I think there’s other things that really struck me. I mean, you know, I have long relations with Mamie Till Mobley, the mother of Emmett Till. And I think the story of Emmett Till is now better known, but what they don’t realize is that the real story is the mother’s strength. At the worst moment of her life, she demanded that they keep that casket open, and she basically reignited the civil rights movement. So I want people to understand that great moments come from the strength of individuals like Mamie Till Mobley.

PHILLIPS:

And everybody will take from the museum, if you’re fortunate enough to visit in person, the moment that they remember the most or that they found the most emotional. For me, and I am sure for many others, seeing Emma Till’s casket in the museum is a gut punch. You don’t recover from very quickly.

BUNCH:

Well, for me, it was really an honor a way to honor his mother, as well as to honor his memory. But I got to know the mother in Chicago, and I was just stunned that this tiny little woman would, at the worst moment of her life, say, how do I help make a country better?

PHILLIPS:

And finally, as a history buff, who, as long as my five- and eight-year-old children cooperate and go to bed when they’re supposed to, if they cooperate, I am end the night by typically reading 10, 15 pages of a history book. So, I can’t have this conversation with one of the best-known historians in our nation without asking, are there a couple of books that have shaped your thinking more than any others that you might encourage me and other listeners to read?

BUNCH:

I think you can’t go wrong with John Hope Franklin. The great eminent historian. His book, From slavery to Freedom, really helped me understand how the African American experience is the quintessential American experience. And I want more people to see these as more inclusive stories rather than ancillary stories. But I also think that if I were reading a book right now, (it would be) David Blight’s biography of Frederick Douglass (Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom). It is without a doubt so important in terms of inspiring us to look at how an individual’s life illuminates. So many things … abolitionism, the fight for women’s suffrage. I’m lucky I get to dip into history almost every night and really use that reservoir to inspire, to challenge, to give me comfort and to give me a sense of hope.

PHILLIPS:

Lonnie, I cannot thank you enough for your generosity of time. And even though it’s not my place to say this to you, I am just so happy that you have been able to achieve what you have and be able to give this nation, with the help of a lot of others, a gift that will live for generations on the National Mall. Thank you.

BUNCH:

Well, thank you. It’s great to talk to you. I really appreciate it.

Back to All EpisodesPublic Speaking Skills Training

Since 2004, we have helped speakers prepare for the world’s biggest stages, including TED, the World Economic Forum, and a presidential announcement speech. We’re committed to your long-term growth, and we’ll be with you every step of the way.

Learn More