Burning Down The House (With a Great Statistic)

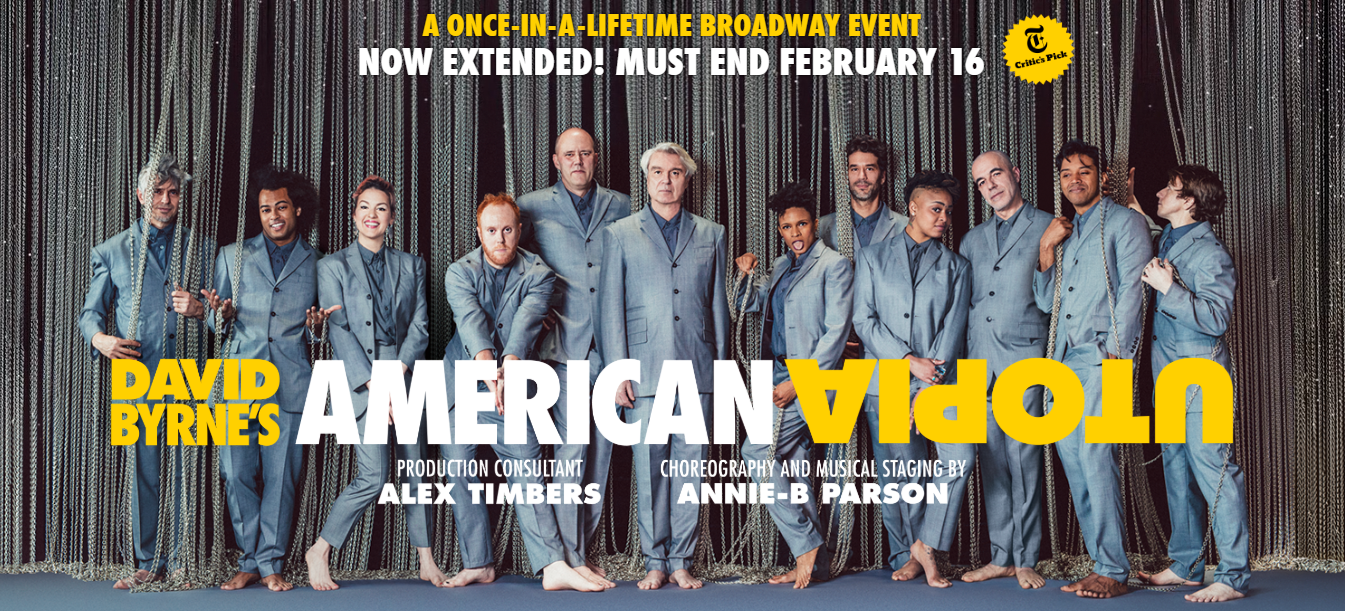

David Byrne, the lead singer for the 1970s – 80s new wave band Talking Heads, is currently starring on Broadway in the superb David Byrne’s American Utopia.

On Sunday, my wife and I saw the show, which features his former band’s music alongside his solo work. It’s easily one of the most energetic, well-choreographed, and sincere events I’ve ever attended.

Toward the end of the show, Byrne paused to talk about voter registration, a cause for which he’s been a longtime advocate. But rather than rattling off statistics and offering banalities, he issued a more memorable audience appeal that is as creative as his music. It went something like this:

“I recently read that about 55 percent of Americans voted in the 2016 election. But for local elections, the number is far lower, about 20 percent.”

Then, he gave instructions to his lighting director.

“Let’s turn the lights up on just this 20 percent of the audience,” he said, pointing to the group in the wings to one side of the stage.

As the rest of the room remained in the dark, the small group in the wings murmured as they were basked in light.

“They seem happy,” Byrne said. “Of course they are. They’re making the rules the rest of you have to follow.”

His lines landed with impact – and were followed with an equally effective call to action. In the lobby, he said, a group called HeadCount was on site to register unregistered voters, a process that would take no longer than a minute or two. Sure enough, the HeadCount folks were impossible to miss when exiting the theater.

While Byrne’s ability to successfully employ statistics to make his case was indeed masterful, it’s a talent anyone can develop with guidance and practice.

How to Use Statistics in Interviews and Presentations

When we coach media spokespersons and public speakers, we encourage them to use supporting evidence, such as statistics. But that’s just the starting point. Statistics, unless they’re truly shocking or counterintuitive, tend not to stick. If we want to maximize the impact of our numbers, we need to present them in ways that go beyond the numbers themselves.

In Made to Stick, Dan and Chip Heath include a line that has, well, stuck with me since I first read it: “Common sense is the enemy of sticky messages.” The problem for Byrne was that most people already know that voter turnout is low. It’s commonsense. He knew that simply saying that wouldn’t elicit a reaction, or an action.

In The Media Training Bible, I offered several additional ways to make your statistics pop. Here are four:

- Make numbers personal: Numbers are often best when reduced to a personal level. Instead of saying a tax cut would save Americans $100 billion this year, say the average family of four would receive $1,250 in tax relief.

- Don’t rely on percentages: Instead of proclaiming that your company’s new energy-efficient manufacturing equipment will cut your plant’s carbon footprint by 35 percent, be more specific. Will that new efficiency save 20,000 gallons of oil this year, enough to fuel 36 company trucks for an entire year? Say so!

- Use ratios: An estimated 170,000 people in Washington, DC, are functionally illiterate. But that number doesn’t tell you much, especially if you have no sense of the overall population. Instead, you might say: “One in three adults living in Washington, DC, is functionally illiterate. Next time you’re on the Metro, look around you. Odds are that the person to your left or right can’t read a newspaper.”

- Provide relative distance: If your car company is introducing an updated model, you’d be proud to announce that the improved version gets four miles more per gallon. But you’d get even more traction if you said, “That’s enough to get from Maine to Miami once per year — without spending an extra penny on gas.”

Statistics — if delivered effectively — have the power to alter perceptions, make people act, and lead to long-lasting change.

Here’s a performance of “Everybody’s Coming To My House,” which is featured in American Utopia, as performed on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.