Neil Armstrong’s Giant Leap for Sound Bites

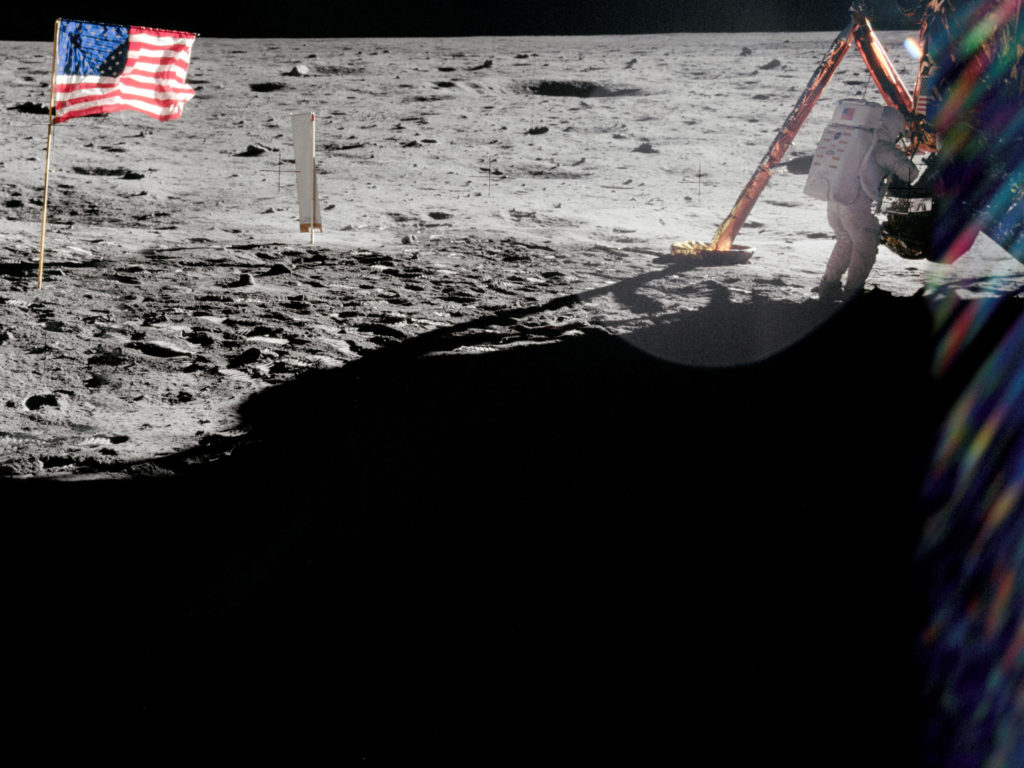

Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin Jr., lunar module pilot of NASA’s first lunar landing mission, stands beside the United States flag. Aldrin and astronaut Neil Armstrong, who is taking the picture, became the first two men to walk on the moon on July 20, 1969. Photo credit: NASA

NASA astronaut Neil Armstrong never quite asked for a do-over, but he contended that the words he uttered upon becoming the first man to walk on the moon lost something in the transmission. On July 20, 1969, as his feet touched down on lunar soil, he memorialized the moment with one of the most famous sound bites in history: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.”

The Apollo 11 mission commander’s line was apparently flubbed. Or, was it? Armstrong, who died in 2012, claimed he added an “a” in front of “man,” but that it wasn’t picked up when it was broadcast to the 650 million people on Earth who were watching the event.

Vexed by the affect, Armstrong knew that without the “a” the phrase was redundant and didn’t make all that much sense. It may have riled grammaticians, but the public issued no outcry. People understood what the sound bite meant in light of the momentous occasion. They didn’t quibble over the aerospace pioneer’s missing indefinite article.

Research over the past 15 years has indicated that perhaps we all got it wrong. In 2006, computer programmer Peter Shann Ford ran Armstrong’s quote through software and detected the missing “a,” even though it was still impossible to hear. (Even Armstrong questioned his own contention later in life.) The discovery was covered in many media reports, including this one from ABC News.

In 2013, a team of researchers at Michigan State University analyzed the sound bite, comparing it to speech patterns of people in central Ohio (where Armstrong was raised). Turns out, they tended to blend the phrase “for a,” so it sounded more like “frrr(uh).” Laura Dilley, an assistant professor in the school’s department of communicative sciences and disorders who led the study, noted that it boosted the astronaut’s side of the story.

Perhaps, after all this time and subsequent study, that sound bite should be considered one of history’s most famous misquotes. Even as esteemed a newscaster as the late Walter Cronkite could have gotten it wrong. After all, he was relaying a quote coming from 240,000 miles away.

Fellow moonwalker Buzz Aldrin catches Armstrong near the lunar module Eagle. Photo credit: NASA

Wherever you fall on this debate, you’ll have plenty of opportunities in the next few days to reconsider or double down on your beliefs. This sound bite has returned in earnest as we celebrate the 50th anniversary celebration of that historic Apollo 11 moon landing. You can hear it here.

U.S. astronaut Neil Armstrong. Photo credit: NASA

In addition to its historical import, it demonstrates the lasting effect of a sound bite that perfectly captures a moment in a memorable and meaningful way. Armstrong could simply have said “We landed,” and all the proper grammar in the world, or Milky Way, for that matter, would not have made that line memorable. Armstrong really would have had something to regret.

We all recognize terrific sound bites because they grab our attention and stick in our memories. They often contain an element of surprise or humor or reflect the Herculean task of compressing a monumental moment into a handful of words.

Not everyone gets the chance to utter such a historic sound bite. However, if you are a spokesperson or subject matter expert, it’s worth having several in your media communications toolbox.

Taking off

It might seem as if those who voice the perfect sound bite have a knack for coming up with witty, off-the-cuff, media-friendly sound bites on the spot. Although Armstrong said he thought up his quote after landing on the surface of the moon, it seems unlikely he improvised it there. We have another inkling of how Armstrong’s line came to be based on interviews that his family gave after his death. In 2012, they told British television channel BBC Two that Armstrong jotted down those words months before the launch.

While some people seem to naturally have the gift of gab, they more than likely worked on those “impromptu” sayings for some time. This part can be difficult – developing a line that conveys a message in a precise and peerless fashion. Keep at it, because a memorable sound bite will last far longer than the time it took to create it.

Here are some tips to get you started:

Search familiar ground

Consider some of the key concepts of your main message and start brainstorming a list of related words. Crack open a dictionary or search an online thesaurus. The more words that go into the till, the more with which you have to work. Look for unexpected pairings, witty combinations, alliteration – just avoid creating a tongue-twister.

Don’t force it

The seeds of great sound bites are all around you, but they can be easy to miss. As your day unfolds, truly listen to the conversations taking place around you, or the ones you are having with colleagues or friends. Somebody else’s castaway comments can be just the jewels you need.

Get them media ready

Reporters are drawn to clever and interesting sound bites, which you can create by using literary devices. Devices such as similes, metaphors, and analogies provide an effective framework upon which to build your sound bite, as does a surprise twist or paradox. Here are a few other tips to create some stellar sound bites.

If done well, your sound bites will last and will always sound smart – a missing “a” or otherwise. They may not last the 50 years Armstrong’s did, but one can always dream. After all, we put a man on the moon.